The future of business is pure chaos. Here’s how you can survive--and perhaps even thrive.

@font-face { font-family: 'FCKaiserCondWebRegular'; src: url('/sites/all/themes/fc_v1/scripts/mod2011/fckaiser-cond-web-regular-webfont.eot'); src: url('/sites/all/themes/fc_v1/scripts/mod2011/fckaiser-cond-web-regular-webfont.eot?#iefix') format('embedded-opentype'), url('/sites/all/themes/fc_v1/scripts/mod2011/fckaiser-cond-web-regular-webfont.woff') format('woff'), url('/sites/all/themes/fc_v1/scripts/mod2011/fckaiser-cond-web-regular-webfont.ttf') format('truetype'), url('/sites/all/themes/fc_v1/scripts/mod2011/fckaiser-cond-web-regular-webfont.svg# FCKaiserCondWebRegular') format('svg'); font-weight: normal; font-style: normal; }

.kaiser {font-family: 'FCKaiserCondWebRegular', Helvetica, sans-serif !important; font-weight: normal; letter-spacing: 1px; line-height:1; font-size:40px; }

.boxxy1, .boxxy2 {width:200px;font-size:14px !important;padding:15px !important;margin:0px;line-height:1.3em !important;float:left;} .boxxy1 span, .boxxy2 span {color:#e8007e;font-weight:bold;}

.dotted {display:block;width:150px;height:3px;margin:5px auto 5px auto;border-bottom:1px dotted #d8d8d8;padding:10px 0px 10px 0px;}

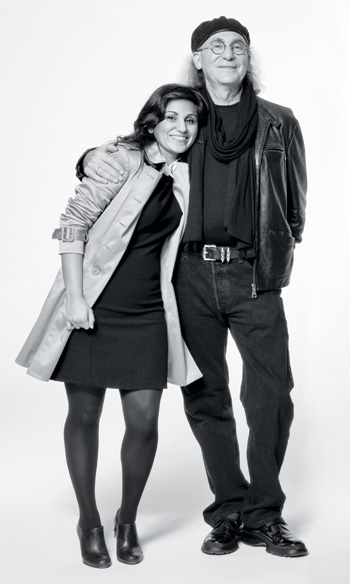

![Members of Generation Flux can be any age and in any industry: From left, Raina Kumra, Bob Greenberg, danah boyd, DJ Patil, Pete Cashmore, Beth Comstock, and Baratunde Thurston. | Photo by Brooke Nipar]() Members of Generation Flux can be any age and in any industry: From left, Raina Kumra, Bob Greenberg, Danah Boyd, DJ Patil, Pete Cashmore, Beth Comstock, and Baratunde Thurston. | Photo by Brooke Nipar, Styling: Krisana Palma; Grooming: Stephanie Peterson

Members of Generation Flux can be any age and in any industry: From left, Raina Kumra, Bob Greenberg, Danah Boyd, DJ Patil, Pete Cashmore, Beth Comstock, and Baratunde Thurston. | Photo by Brooke Nipar, Styling: Krisana Palma; Grooming: Stephanie Peterson

DJ Patil pulls a 2-foot-long metal bar from his backpack. The contraption, which he calls a "double pendulum," is hinged in the middle, so it can fold in on itself. Another hinge on one end is attached to a clamp he secures to the edge of a table. "Now," he says, holding the bar vertically, at its top, "see if you can predict where this end will go." Then he releases it, and the bar begins to swing wildly, circling the spot where it is attached to the table, while also circling in on itself. There is no pattern, no way to predict where it will end up. While it spins and twists with surprising velocity, Patil talks to me about chaos theory. "The important insight," he notes, "is identifying when things are chaotic and when they're not."

In high school, Patil got kicked out of math class for being disruptive. He graduated only by persuading his school administrator to change his F grade in chemistry. He went to junior college because that's where his girlfriend was going, and signed up for calculus because she had too. He took so long to do his homework, his girlfriend would complain. "It's not like I'm going to become a mathematician," he would tell her.

Chaotic disruption is rampant, not simply from the likes of Apple, Facebook, and Google.

Patil, 37, is now an expert in chaos theory, among other mathematical disciplines. He has applied computational science to help the Defense Department with threat assessment and bioweapons containment; he worked for eBay on web security and payment fraud; he was chief scientist at LinkedIn, before joining venture-capital firm Greylock Partners. But Patil first made a name for himself as a researcher on weather patterns at the University of Maryland: "There are some times," Patil explains, "when you can predict weather well for the next 15 days. Other times, you can only really forecast a couple of days. Sometimes you can't predict the next two hours."

The business climate, it turns out, is a lot like the weather. And we've entered a next-two-hours era. The pace of change in our economy and our culture is accelerating--fueled by global adoption of social, mobile, and other new technologies--and our visibility about the future is declining. From the rise of Facebook to the fall of Blockbuster, from the downgrading of U.S. government debt to the resurgence of Brazil, predicting what will happen next has gotten exponentially harder. Uncertainty has taken hold in boardrooms and cubicles, as executives and workers (employed and unemployed) struggle with core questions: Which competitive advantages have staying power? What skills matter most? How can you weigh risk and opportunity when the fundamentals of your business may change overnight?

![When conditions are chaotic, Patil explains, you must apply different techniques.]()

When conditions are chaotic, Patil explains, you must apply different techniques. "Command-and-control hierarchical structures are being disintegrated," says boyd. | Photo by Brooke Nipar

danah boyd, 34 Senior Researcher, Microsoft Research Studied at Brown, MIT Media Lab, and UC Berkeley; named "High Priestess of the Internet" by the Financial Times; has advised Intel, Google, Yahoo, and more; worked on V-Day, a not-for-profit focused on ending violence against women and girls. "People ask me, 'Are you afraid you're going to get fired?' That's the whole point: not to be afraid." More »

DJ Patil, 37 Data Scientist, Greylock Partners Researcher at Los Alamos; Defense Department fellow; virtual librarian for Iraq; web-security architect for eBay; head of data team at LinkedIn, where his team created People You May Know. "I don't have a plan. If you look too far out in the future, you waste your time."More »

Look at the global cell-phone business. Just five years ago, three companies controlled 64% of the smartphone market: Nokia, Research in Motion, and Motorola. Today, two different companies are at the top of the industry: Samsung and Apple. This sudden complete swap in the pecking order of a global multibillion-dollar industry is unprecedented. Consider the meteoric rise of Groupon and Zynga, the disruption in advertising and publishing, the advent of mobile ultrasound and other "mHealth" breakthroughs (see "Open Your Mouth And Say 'Aah!'). Online-education efforts are eroding our assumptions about what schooling looks like. Cars are becoming rolling, talking, cloud-connected media hubs. In an age where Twitter and other social-media tools play key roles in recasting the political map in the Mideast; where impoverished residents of refugee camps would rather go without food than without their cell phones; where all types of media, from music to TV to movies, are being remade, redefined, defended, and attacked every day in novel ways--there is no question that we are in a new world.

Any business that ignores these transformations does so at its own peril. Despite recession, currency crises, and tremors of financial instability, the pace of disruption is roaring ahead. The frictionless spread of information and the expansion of personal, corporate, and global networks have plenty of room to run. And here's the conundrum: When businesspeople search for the right forecast--the road map and model that will define the next era--no credible long-term picture emerges. There is one certainty, however. The next decade or two will be defined more by fluidity than by any new, settled paradigm; if there is a pattern to all this, it is that there is no pattern. The most valuable insight is that we are, in a critical sense, in a time of chaos.

To thrive in this climate requires a whole new approach, which we'll outline in the pages that follow. Because some people will thrive. They are the members of Generation Flux. This is less a demographic designation than a psychographic one: What defines GenFlux is a mind-set that embraces instability, that tolerates--and even enjoys--recalibrating careers, business models, and assumptions. Not everyone will join Generation Flux, but to be successful, businesses and individuals will have to work at it. This is no simple task. The vast bulk of our institutions--educational, corporate, political--are not built for flux. Few traditional career tactics train us for an era where the most important skill is the ability to acquire new skills.

DJ Patil is a GenFluxer. He has worked in academia, in government, in big public companies, and in startups; he is a technologist and a businessman; a teacher and a diplomat. He is none of those things and all of them, and who knows what he will be or do next? Certainly not him. "That doesn't bother me," he says. "I'll find something."

The New Economy Is For Real More than 15 years ago, this magazine was launched with a cover that declared: "Work Is Personal. Computing Is Social. Knowledge Is Power." Those words resonate today, but with a new, deeper meaning. Fast Company's covers during the dotcom boom of the 1990s described "Free Agent Nation" and "The Brand Called You." We became associated with the "new economy," with the belief that the world had changed irreparably, and that yesterday's rules no longer applied. But then the dotcom bubble burst in 2000, and the idea of a new economy was discredited.

![]()

"In a big company, you never feel fast enough," says Comstock. Notes Thurston, "To see what you can't see coming, you've got to embrace larger principles." | Photo by Brooke Nipar

Baratunde Thurston, 34 Director of Digital, The Onion Harvard philosophy major turned consultant turned stand-up comedian. Mayor of the Year on Foursquare. The promo letter for his new book, How to Be Black, begins, "If you don't buy this book, you're racist." "I can't wait for the middle-management level to die off and the next generation gets in there.

Then we'll have a revolution." More »

Beth Comstock, 51 Chief Marketing Officer, GE TV news reporter turned PR pro turned marketing powerhouse. She's responsible for Ecomagination and Healthymagination, GE efforts that account for billions of dollars in sales. "Today everyone feels out of control. Some people say, 'I declare bankruptcy.' But they're not embracing change. They're giving up." "More »

Now we know that what we saw in the 1990s was not a mirage. It was instead a shadow, a premonition of a new business reality that is emerging every day--and this time, perhaps chastened by that first go-round, we're prepared to admit that we don't fully understand it. This new economy currently revolves around social and mobile, but those may be only the latest manifestations of a global, connected world careening ahead at great velocity.

Some pundits deride the current era as just another bubble. They point out that new, heady tech companies are garnering massive valuations: Facebook, Groupon, LinkedIn. And beyond the alpha dogs, the list of startups with valuations above $200 million is long indeed: Airbnb, Dropbox, Flipboard, Foursquare, Gilt Groupe, Living Social, Rovio, Spotify--the roster goes on and on.

We are under constant pressure to learn new things. It can be daunting. It can be exhilarating.

Setting aside the fact that the majority of these enterprises, unlike the darlings of the late-1990s, have significant revenue, so what if some companies are overvalued? That still doesn't discount the way mobile, social, and other breakthroughs are changing our way of life, not just in America but around the globe. And in the process, these changes are remaking geopolitical and business assumptions that have been in place for decades. This was not true in 2000. But it is now. Chaotic disruption is rampant, not simply from the likes of Apple, Facebook, and Google. No one predicted that General Motors would go bankrupt--and come back from the abyss with greater momentum than Toyota. No one in the car-rental industry foresaw the popularity of auto-sharing Zipcar--and Zipcar didn't foresee the rise of outfits like Uber and RelayRides, which are already trying to steal its market. Digital competition destroyed bookseller Borders, and yet the big, stodgy music labels--seemingly the ground zero for digital disruption--defy predictions of their demise. Walmart has given up trying to turn itself into a bank, but before retail bankers breathe a sigh of relief, they ought to look over their shoulders at Square and other mobile-wallet initiatives. Amid a reeling real-estate market, new players like Trulia and Zillow are gobbling up customers. Even the law business is under siege from companies like LegalZoom, an online DIY document service. "All these industries are being revolutionized," observes Pete Cashmore, the 26-year-old founder of social-news site Mashable, which has exploded overnight to reach more than 20 million users a month. "It's come to technology first, but it will reach every industry. You're going to have businesses rise and fall faster than ever."

You Don't Know What You Don't Know "In a big company, you never feel you're fast enough." Beth Comstock, the chief marketing officer of GE, is talking to me by phone from the Rosewood Hotel in Menlo Park, California, where she's visiting entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley. She gets a charge out of the Valley, but her trips also remind her how perilous the business climate is right now. "Business-model innovation is constant in this economy," she says. "You start with a vision of a platform. For a while, you think there's a line of sight, and then it's gone. There's suddenly a new angle."

Within GE, she says, "our traditional teams are too slow. We're not innovating fast enough. We need to systematize change." Comstock connected me with Susan Peters, who oversees GE's executive-development effort. "The pace of change is pretty amazing," Peters says. "There's a need to be less hierarchical and to rely more on teams. This has all increased dramatically in the last couple of years."

![]()

![]()

Executives at GE are bracing for a new future. The challenge they face is the same one staring down wide swaths of corporate America, not to mention government, schools, and other institutions that have defined how we've lived: These organizations have structures and processes built for an industrial age, where efficiency is paramount but adaptability is terribly difficult. We are finely tuned at taking a successful idea or product and replicating it on a large scale. But inside these legacy institutions, changing direction is rough. From classrooms arranged in rows of seats to tenured professors, from the assembly line to the way we promote executives, we have been trained to expect an orderly life. Yet the expectation that these systems provide safety and stability is a trap. This is what Comstock and Peters are battling.

"The business community focuses on managing uncertainty," says Dev Patnaik, cofounder and CEO of strategy firm Jump Associates, which has advised GE, Target, and PepsiCo, among others. "That's actually a bit of a canard." The true challenge lies elsewhere, he explains: "In an increasingly turbulent and interconnected world, ambiguity is rising to unprecedented levels. That's something our current systems can't handle.

"There's a difference between the kind of problems that companies, institutions, and governments are able to solve and the ones that they need to solve," Patnaik continues. "Most big organizations are good at solving clear but complicated problems. They're absolutely horrible at solving ambiguous problems--when you don't know what you don't know. Faced with ambiguity, their gears grind to a halt.

You don't need to be a jack-of-all-trades to flourish now. But you do need to be open-minded.

"Uncertainty is when you've defined the variable but don't know its value. Like when you roll a die and you don't know if it will be a 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. But ambiguity is when you're not even sure what the variables are. You don't know how many dice are even being rolled or how many sides they have or which dice actually count for anything." Businesses that focus on uncertainty, says Patnaik, "actually delude themselves into thinking that they have a handle on things. Ah, ambiguity; it can be such a bitch."

Be Not Afraid What's "a bitch" for companies can be terror for individuals. The idea of taking risks, of branching out into this ambiguous future, is scary at a moment when the economy is in no hurry to emerge from the doldrums and when unemployment is a national crisis. The security of the 40-year career of the man in the gray-flannel suit may have been overstated, but at least he had a path, a ladder. The new reality is multiple gigs, some of them supershort (see "The Four-Year Career"), with constant pressure to learn new things and adapt to new work situations, and no guarantee that you'll stay in a single industry. It can be daunting. It can be exhausting. It can also be exhilarating. "Fear holds a lot of people back," says Raina Kumra, 34. "I'm skill hoarding. Every time I update my resume, I see the path that I didn't know would be. You keep throwing things into your backpack, and eventually you'll have everything in your tool kit."

Kumra is sitting in a Dublin hotel, where earlier she spoke on a panel about the future of mobile before a group of top chief information officers. She is not technically in the mobile business; nor is she a software engineer or an academic. She actually works for a federal agency, the Broadcasting Board of Governors, as codirector of innovation for the group that oversees Voice of America and other government-run media. How she got there is a classic journey of flux.

Kumra started out in film school. She made two documentaries, including one in South America and India, and then took a job as a video editor for Scientific American Frontiers. "After each trip to shoot footage," she says, "I'd come back and find that the editing tools had all changed." So she decided to learn computer programming. "I figured I had to get my tech on," says Kumra, who signed up for New York University's Interactive Telecommunications Program. She then moved into the ad world, doing digital campaigns at BBH, R/GA, and Wieden+Kennedy before launching her own agency. Along the way she picked up a degree from Harvard's design school, taught at the University of Amsterdam, and started a not-for-profit called Light Up Malawi.

"So many people tell me, 'I don't know what you do,'" Kumra says. It's an admission echoed by many in Generation Flux, but it doesn't bother her at all. "I'm a collection of many things. I'm not one thing."

The point here is not that Kumra's tool kit of skills allows her to cut through the ambiguity of this era. Rather, it is that the variety of her experiences--and her passion for new ones--leaves her well prepared for whatever the future brings. "I had to try something entrepreneurial. I had to try social enterprise. I needed to understand government," she says of her various career moves. "I just needed to know all this."

You do not have to be a jack-of-all-trades to flourish in the age of flux, but you do need to be open-minded. GE's Comstock doesn't have as eclectic a career path as Kumra--she has spent two decades within GE's various divisions. But just because she can dress and act the part of a loyal corporate soldier doesn't mean Comstock is not a GenFluxer. She's got a sweet spot for creative types, especially those whose fresh thinking can spur the buttoned-up GE culture forward. She's brought in folks like Benjamin Palmer, the groovy CEO of edgy ad firm Barbarian Group, to help inject new ideas and processes into GE's marketing apparatus. "We're creating digital challenge teams," she explains. "We're doing a lot more work with entrepreneurs. It's part of our internal growth strategy. It creates tension. It makes people's jobs frustrating. But it's also energizing."

![Cashmore's Mashable is part of a class of new, fast-rising firms, from Airbnb to Dropbox, Living Social to Spotify, Flipboard to Foursquare. | Photo by Brooke Nipar]()

Cashmore's Mashable is part of a class of new, fast-rising firms, from Airbnb to Dropbox, Living Social to Spotify, Flipboard to Foursquare. | Photo by Brooke Nipar

Pete Cashmore, 26 CEO, Mashable At 19, he founded a tech blog in Scotland, which has grown into a monster site for social news. Mashable has more than 2 million Twitter followers. "I don't have any personal challenges about throwing away the past. If you're not changing, you're giving others a chance to catch up." More »

Comstock, once president of digital media at NBC, is now one of CEO Jeff Immelt's key confidants. "I've always gravitated to the new," Comstock says, in trying to explain her comfort with change. "Part of it is who you are. I grew up in media, in news, and developed almost an addiction to go from deadline to deadline. It's intoxicating." And profitable. Comstock is the architect of Ecomagination and Healthymagination, GE initiatives that have helped reconfigure the company during this financial crisis. While it's too early to tell what Healthymagination could produce, the Ecomagination group has to date accounted for $85 billion in revenue.

Nuke Nostalgia If ambiguity is high and adaptability is required, then you simply can't afford to be sentimental about the past. Future-focus is a signature trait of Generation Flux. It is also an imperative for businesses: Trying to replicate what worked yesterday only leaves you vulnerable.

Baratunde Thurston is a quintessential GenFluxer. When I met up with him recently, he had just pulled an all-nighter. At 1 a.m. that morning, the New York City police had descended on Zuccotti Park to roust the Occupy Wall Street crowd, and Thurston--who is digital director for satirical news outlet The Onion--was called on to help cover the event. He was at home, in Brooklyn, but he didn't jump on the subway or into a taxi to hustle his way to lower Manhattan like a traditional journalist. Instead he fired up his computer. "I found the live streams of video from the site, so I could see what was going on. Then I monitored police scanners, to hear what they were saying. I looked at news feeds and Mayor Bloomberg's statements, and then I accessed all my social-media feeds, screening by zip code what people down there were saying. Some people in the neighborhood were freaked out by helicopters overhead, shining floodlights into their windows. They had no idea what was going on, said it felt like a police action. Which it was, you know."

Industries are being revolutionized," says Cashmore. "Businesses will rise and fall faster than ever."

For three hours, Thurston pieced together what he was seeing and hearing, and rebroadcasted it via digital channels. "I had a better sense of what was happening and where the crowds were moving than the people on the ground," he says. By eschewing well-trod practices and creatively adjusting to a fluid situation, he built an authentic narrative in real time, one that reflected the true story far better than the nightly TV news.

Thurston calls himself "a politically active, technology-loving comedian from the future." He works for The Onion, does stand-up comedy, and has a terrific book coming out this month called How to Be Black. "I was a computer programmer in high school, but I discovered I wasn't very good at it--it was too tedious," he says. "I was a philosophy major. I did management consulting right out of college. But then I started doing comedy, and I love it. People say to me all the time, 'What are you? You need to focus.' Maybe so. But for now, this smorgasbord of activities is working."

![]()

![]()

Thurston is telling me all this over lunch at Delicatessen, a restaurant in SoHo on the corner of Prince and Lafayette. "I'm the mayor of this corner on Foursquare. Last night, the Occupy crowd walked right by here, and I tweeted them: 'That's my corner. Sorry I'm not there, I promise I'd be a better mayor for you than Bloomberg.'"

Thurston is not bashful. At 34, he's not a kid (though he says, "I have the technological age of a 26-year-old"). And he's cheering on the pace of change. "You can knock on the doors of power and make your case for access. That's the way it's usually done. Or you can be like Mark Zuckerberg and build your own system around it." Thurston is utterly lacking in nostalgia. "I was talking to some documentary filmmakers at a conference, and they all just talk about loss, the loss of a model. I can empathize. But I'm not upset that the model is dying. The milkman is dead, but we drink more milk than ever. Do we really want to return to a world of just three broadcast channels?"

Nostalgia is a natural human emotion, a survival mechanism that pushes people to avoid risk by applying what we've learned and relying on what's worked before. It's also about as useful as an appendix right now. When times seem uncertain, we instinctively become more conservative; we look to the past, to times that seem simpler, and we have the urge to re-create them. This impulse is as true for businesses as for people. But when the past has been blown away by new technology, by the ubiquitous and always-on global hypernetwork, beloved past practices may well be useless.

Nostalgia is of particular concern to GE's Peters, keeper of the company's vaunted leadership training. Since 2009, she has been aggressively rethinking the program; last January, she rolled out "a new contemporized view of expectations" for GE's top 650 managers. That's a mouthful, but basically it's a revolution to the way execs are evaluated at the company known as America's leadership factory. "We now recognize that external focus is more multifaceted than simply serving 'the customer,'" says Peters, "that other stakeholders have to be considered. We talk about how to get and apply external knowledge, how to lead in ambiguous situations, how to listen actively, and the whole idea of collaboration."

Not everyone at GE is excited about the shift. "Some people question changing our definitions," Peters says. "When they do, I ask: How many of you use the same cell phone from five years ago? The world isn't the same, so we need new parameters." At GE's Crotonville leadership center, in New York, "we are physically changing the buildings, to make it better for teams," she says. A large kitchen has been installed, so teams can cook together "with all the messiness and egalitarian spirit involved." Managers who are uncomfortable playing second fiddle to more culinary-inclined staffers "can sit on the side and have a glass of wine," says Peters. "But usually, after a while, they realize they're on the sidelines, and they get in the game." And then there's the building known around campus as the "White House," which dates back to the 1950s. "It's where executives would go after dinner to have a drink," Peters explains. "We're gutting it, replacing it with a university-like all-day coffeehouse. Some colleagues who've been here for 20, 30 years, they tell me, 'This is terrible.' I tell them, 'You are not our target demographic.'"

![Kumra, who has had her DNA sequence read, actually has a risk taker's gene; Greenberg may not have that gene, but he's taken decades' worth of risks. | Photo by Brooke Nipar]()

Kumra, who has had her DNA sequence read, actually has a risk taker's gene; Greenberg may not have that gene, but he's taken decades' worth of risks. | Photo by Brooke Nipar

Raina Kumra, 34 Codirector of Innovation, Broadcasting Board of Governors The documentary filmmaker, digital strategy guru at Wieden+Kennedy, and founder of Light Up Malawi is now a civil servant. "I work on a mission: to use mass platforms to change the world. It's a mission, not a job title, not a career."More »

Bob Greenberg, 63 CEO and founder, R/GA After founding his firm to create visual effects for movies like Alien and Zelig, he now delivers cutting-edge digital programs for Nike, Nokia, HP, and more. "People talk about change and adaptation, but they have more competition than they think." More »

So much for nostalgia. At this year's meeting of GE's top executives, presentation materials will be available only via iPads. "Some are scrambling to learn how to turn one on," Peters says. "They just have to do it. There's a natural tendency for some people to pull back when change comes. We're not going to wave a magic wand and make everyone different. But with the right team, the right coaching, we can get them to see things differently."

Thurston is less forgiving of the iPad-challenged. "It's irresponsible not to use the tools of the day," he charges. "People say, 'Oh, if I master Twitter, I've got it figured out.' That's right, but it's also so wrong. If you master those things and stop, you're just going to get killed by the next thing. Flexibility of skills leads to flexibility of options. To see what you can't see coming, you've got to embrace larger principles."

There Are No Perfect Role Models Bob Greenberg, chief executive of digital advertising agency R/GA, doesn't do the comb-over. Nor does he crop his hair short or shave his scalp, in the way of so many modern admen. Instead, beyond the patch of baldness on top of his head, his hair is long and flowing and bushy. It's as if he's saying, Look, I am who I am. So deal with it.

I met with Greenberg several times this past fall to talk about how he's managing a growing business in an industry experiencing total upheaval. The first time we sat down, in September, he dropped that his company had dozens of job openings. The agency, Greenberg explained, had grown 20% since the start of the year, from 1,000 staffers to 1,200. And to net those 200 additions, Greenberg had hired 500 new people. That math doesn't exactly add up, I pointed out.

Here's the rub: R/GA's young GenFlux staffers are leaving at such a steady pace, sticking around for such short runs that Greenberg finds himself constantly replacing them, endlessly slotting one talented young person into another's place. Many CEOs would react to this news with alarm: What are we doing wrong? Why can't we keep our young talent? Greenberg talks about this intense transition with nonchalance. He's not upset by it; he's not fighting it; and he assumes this is the way life will be for the foreseeable future.

![]()

But that doesn't mean he's standing still. Despite strong business momentum, he's pushing R/GA into a radical reorganization--the fifth time he's hauled the firm into a new business model. "If we don't change our structure, we'll get less relevant," Greenberg tells me. "We won't be able to grow." This time, he's integrating 12 new capabilities, from live events to data visualization to product development, into R/GA's platforms. "People talk about change and adaptation, but they don't see how fast the competition is coming," he says. "We have to move. We have no choice."

R/GA's flexibility is instructive for large firms and small. Many businesses are struggling to recast their strategies, with top execs hunting desperately for successful models that they can replicate. (Which might explain why you've probably heard the phrase, "We're the Apple of . . ." once too often.) But there is no new model; you may well need to build one from scratch. "Command-and-control hierarchical structures are being disintegrated," says danah boyd, a social-science researcher for Microsoft Research who also teaches at New York University. "There's a difference between the old broadcast world and the networked world."

In a world of flux, what succeeds for one industry or company doesn't necessarily work for another; and even if it does, it may not work for long. One reason Facebook has thrived is that it is continually changing. Users and pundits routinely carp about new features or designs. But this is the way Facebook has been from its inception--including the critical decision in 2006 to open its doors to those not in college. Mark Zuckerberg knows that if he doesn't keep Facebook moving, others will come after him. Steve Jobs applied a similar approach at Apple: He disrupted his own business in dozens of ways, from refusing to make new products compatible with old operating systems to dumping the iPod's successful track wheel to embrace touch screens--ahead of everyone else.

Just because a specific tactic worked for Apple doesn't mean it is right for your business. Maybe the world's best marshmallow maker just needs to keep churning out the best marshmallow (even if it should have its own Facebook page and a Twitter feed). Every enterprise needs to find--and evolve--the structure, system, and culture that best allows it to stay competitive as its specific market shifts. Business leaders need to be creative, adaptive, and focused in their techniques, staffing, and philosophy.

Given the need for more iteration, missteps like Netflix's may become more prevalent.

An instructive analogy comes from the world of software. In a recent book called Building Data Science Teams, chaos expert Patil explained how software used to be developed: "One group defines the product, another builds visual mock-ups . . . and finally a set of engineers builds it to some specification document." This is known as a "waterfall" process, which was practiced by large, successful enterprises like Microsoft that, on a designated schedule, issued large, finished releases of their products (Windows 95, Windows 2000, and so on). Today that process is giving way to "agile" development, to what Patil calls "the ability to adapt and iterate quickly throughout the product life cycle." In software, such work follows the precepts of "The Agile Manifesto," a 2001 document written by a group of developers who stated a preference for "individuals and interactions over processes and tools; working software over comprehensive documentation; [and] responding to change over following a plan."

It's not just the apps on your iPad: The entire world of business is now in a constant state of agile development. New releases are constant; tweaks, upgrades, and course corrections take place on the fly. There is no status quo; there is only a process of change.

But if your business is primed to be adaptable, flexible, and prepared for any shift in the economy, isn't it also primed to be whipsawed by constant change?

I visited Nike CEO Mark Parker on the company's campus outside of Portland, Oregon, and I asked if he had ever considered having Nike-branded hospitals, or Nike-branded doctors, or Nike-branded health food. After all, Nike is dedicated to improving its customers' health. The health-care business is in tumult, and presumably an innovative new entrant could make a lot of money. Parker replied that, however tempting those business opportunities might be, they didn't intersect with Nike's core focus on sport.

That doesn't mean Nike is avoiding new areas--including ones that touch on health. Spread across a couple of buildings on the west side of its campus are the employees of Nike's digital sports operation. This burgeoning startup is focused on remaking how casual athletes train, stay motivated, and connect with one another. More than 5 million people interact on the Nike+ website, which connects to sensors in your shoes, phone, or watch to provide GPS-linked data about your exercise, as well as health facts such as heart rate and calories burned. By deploying new technologies and tools in the service of its long-term mission, Nike has deepened its customers' brand experience--and reinforced, rather than fractured, its sense of identity.

The key is to be clear about your business mission. In a world of flux, this becomes more important than ever. Netflix's recent troubles with its ill-fated Qwikster product is a telling example. Netflix's core proposition has always been delivering a better, simpler, cheaper consumer experience. CEO Reed Hastings rattled video stores like Blockbuster with his no-late-fee DVD-by-mail model; he then obliterated them with his embrace of online streaming. But along the way, Netflix began to see itself as a first-mover technology leader more than a leader in consumer-focused experiences. That's when the company stumbled, by forcing its customers to go somewhere they didn't want, more because it made sense for Netflix's business model than it did for them.

The twist to all this: Given the need for more frequent iteration in our age of flux, missteps like Netflix's may become more prevalent. And over time, we'll become more forgiving as a result. That will encourage even greater embrace of innovation by businesses, as the costs of failure decline. And in the process, flux will destabilize--and energize--our economy even more.

Lessons Of Flux Our institutions are out of date; the long career is dead; any quest for solid rules is pointless, since we will be constantly rethinking them; you can't rely on an established business model or a corporate ladder to point your way; silos between industries are breaking down; anything settled is vulnerable.

Put this way, the chaos ahead sounds pretty grim. But its corollary is profound: This is the moment for an explosion of opportunity, there for the taking by those prepared to embrace the change. We have been through a version of this before. At the turn of the 20th century, as cities grew to be the center of American culture, those accustomed to the agrarian clock of sunrise-sunset and the pace of the growing season were forced to learn the faster ways of the urban-manufacturing world. There was widespread uneasiness about the future, about what a job would be, about what a community would be. Fringe political groups and popular movements gave expression to that anxiety. Yet from those days of ambiguity emerged a century of tremendous progress.

Today we face a similar transition, this time born of technology and globalization--an unhinging of the expected, from employment to markets to corporate leadership. "There are all kinds of reasons to be afraid of this economy," says Microsoft Research's boyd. "Technology forces disruption, and not all of the change will be good. Optimists look to all the excitement. Pessimists look to all that gets lost. They're both right. How you react depends on what you have to gain versus what you have to lose."

Yet while pessimists may be emotionally calmed by their fretting, it will not aid them practically. The pragmatic course is not to hide from the change, but to approach it head-on. Thurston offers this vision: "Imagine a future where people are resistant to stasis, where they're used to speed. A world that slows down if there are fewer options--that's old thinking and frustrating. Stimulus becomes the new normal."

To flourish requires a new kind of openness. More than 150 years ago, Charles Darwin foreshadowed this era in his description of natural selection: "It is not the strongest of the species that survives; nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change." As we traverse this treacherous, exciting bridge to tomorrow, there is no clearer message than that.

A version of this article appears in the February 2012 issue of Fast Company.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Members of Generation Flux can be any age and in any industry: From left, Raina Kumra, Bob Greenberg, Danah Boyd, DJ Patil, Pete Cashmore, Beth Comstock, and Baratunde Thurston. | Photo by Brooke Nipar, Styling: Krisana Palma; Grooming: Stephanie Peterson

Members of Generation Flux can be any age and in any industry: From left, Raina Kumra, Bob Greenberg, Danah Boyd, DJ Patil, Pete Cashmore, Beth Comstock, and Baratunde Thurston. | Photo by Brooke Nipar, Styling: Krisana Palma; Grooming: Stephanie Peterson  When conditions are chaotic, Patil explains, you must apply different techniques. "Command-and-control hierarchical structures are being disintegrated," says boyd. | Photo by Brooke Nipar

When conditions are chaotic, Patil explains, you must apply different techniques. "Command-and-control hierarchical structures are being disintegrated," says boyd. | Photo by Brooke Nipar  "In a big company, you never feel fast enough," says Comstock. Notes Thurston, "To see what you can't see coming, you've got to embrace larger principles." | Photo by Brooke Nipar

"In a big company, you never feel fast enough," says Comstock. Notes Thurston, "To see what you can't see coming, you've got to embrace larger principles." | Photo by Brooke Nipar

Cashmore's Mashable is part of a class of new, fast-rising firms, from Airbnb to Dropbox, Living Social to Spotify, Flipboard to Foursquare. | Photo by Brooke Nipar

Cashmore's Mashable is part of a class of new, fast-rising firms, from Airbnb to Dropbox, Living Social to Spotify, Flipboard to Foursquare. | Photo by Brooke Nipar

Kumra, who has had her DNA sequence read, actually has a risk taker's gene; Greenberg may not have that gene, but he's taken decades' worth of risks. | Photo by Brooke Nipar

Kumra, who has had her DNA sequence read, actually has a risk taker's gene; Greenberg may not have that gene, but he's taken decades' worth of risks. | Photo by Brooke Nipar

Photo by Brooke Nipar

Photo by Brooke Nipar

To install Pret's incentive system in the academy would be to blow it up.

To install Pret's incentive system in the academy would be to blow it up.

Nicholas Kristof has been writing for The New York Times for more than a quarter century and has appeared on that paper's op-ed page since 2001, often penning articles about the struggles of people in distant parts of the world. He has even been dubbed the "moral conscience" of his generation of journalists. Less well known is his role as an innovator in journalism. In 2003, he became

Nicholas Kristof has been writing for The New York Times for more than a quarter century and has appeared on that paper's op-ed page since 2001, often penning articles about the struggles of people in distant parts of the world. He has even been dubbed the "moral conscience" of his generation of journalists. Less well known is his role as an innovator in journalism. In 2003, he became  How will the game work?

How will the game work?

William Joyce once helped design Woody and Buzz Lightyear. But now he's taking on giants like his former employer, Pixar, from an unlikely base: Shreveport, Louisiana, where he and his team at Moonbot Studios are intentionally acting nothing like a typical studio.

William Joyce once helped design Woody and Buzz Lightyear. But now he's taking on giants like his former employer, Pixar, from an unlikely base: Shreveport, Louisiana, where he and his team at Moonbot Studios are intentionally acting nothing like a typical studio. A scene from Lessmore, in which Morris discovers a house full of living, eager books.

A scene from Lessmore, in which Morris discovers a house full of living, eager books.