Uniqlo is gaining on Zara, H&M, and Gap as the world's king of casual clothing. But can Tadashi Yanai ride toasty, dry underwear to $50 billion in revenue by 2020?

Uniqlo founder Yanai uses design and technology to improve upon classic American sportswear--and now he wants to sell it back to Americans. | Photo by Kareem Black

Uniqlo founder Yanai uses design and technology to improve upon classic American sportswear--and now he wants to sell it back to Americans. | Photo by Kareem Black

On a drizzly Wednesday afternoon in Tokyo, Tadashi Yanai is hunting for hamburgers. We're in the Tokyo Midtown mall, speed-walking through a brightly lit Uniqlo store--one of 1,100 in the global clothing chain he has built over the past 30 years.

"A hamburger can have just a patty only," Yanai had told me a few minutes earlier, 31 stories upstairs in his office. "Or maybe it has pickles or lettuce! You may want ketchup or mustard--you name it!--depending on your taste. You definitely want more than buns and patty. Only then can you have a great hamburger."

I don't think we're headed to the food court. Yanai, who can speak in koans, is talking about Uniqlo's proletarian sportswear, which is all around us.

"Too often, we have tended to fall into a trap of creating plain hamburgers." Yanai zeroes in on a lumpen gray sweatsuit, a 1,490-yen ($20) example of what to wear if you want to void all attractiveness on your person. "This," he says almost triumphantly, "is a plain hamburger. It's got nothing. You see no trace of a design commitment. We are probably selling it because it sold well last year." He pauses, and then looks at me. "Would you wear it?"

"No," I say. "Would you?"

"Of course not!" he says. "And my point is that I'm still not satisfied with it. It's still not finished."

I ask him to show me a once-plain hamburger that's been transformed. He thinks for a moment and then darts to a corner of the store that, from afar, looks like a Pantone color grid and, up close, is a set of cubbyholes packed with socks. "We started out with a few different colors," he says, "but then we came up with this crazy idea: Why not 50 colors instead of 10?" The rainbow of hosiery is at least a Five Guys burger.

Uniqlo Street Style

Then Yanai gets a better idea and zips over to a wall of underwear. "Our underwear used to just be cotton, but we wanted to see if we could create something out of synthetics," he says. With the Japanese materials-science company Toray Industries, Uniqlo created a stretchy fabric called Silky Dry, a name that pretty much explains how it's supposed to feel, even when the wearer is Sweaty Gross. (Uniqlo is in the process of rebranding it "Airism.") "I wear it every day," Yanai says. "It makes customers happy--and that makes me happy."

Before I can process the relationship between this CEO's undergarments and his happiness, Yanai plucks a packet of black boxer briefs from the display. "This will be my gift to you," he says, with the enthusiasm worthy of a foie-gras burger. "I encourage you to put it on!"

The best example of a hamburger transformed may be Uniqlo itself. Fifteen years ago, it was, according to one Uniqlo exec, "like the Old Navy of Japan, but not as nice." Uniqlo didn't even have a Tokyo store. Today, it sells socks, underwear, T-shirts, jeans, blazers, and dresses in 12 countries. Despite that sweatsuit, it has appeared on innumerable fashion hot lists, having scored much-praised collaborations with designers including Jil Sander and Charlotte Ronson. It offers perhaps the most technologically advanced textiles of any mass-market retailer in the world. And the results have been dramatic: In fiscal 2012, Uniqlo is expected to tally about $10 billion in revenue and $1.5 billion in profit, making it the world's fourth-largest clothing retailer, after Zara, H&M, and Gap.

None of this is enough to satisfy Yanai. By 2020, he wants to quintuple Uniqlo's worldwide revenue. He is aggressively exporting Uniqlo's everyman, everywoman, and everychild style around the globe. In June, Uniqlo opened its first store in the Philippines. Next up: Indonesia, Vietnam, and, later, India. "This is the big flow of history," he says of his expansion into Asia and his wooing of its burgeoning middle class.

“America, for me, is the country where, if you have something great to offer, you’ll be valued highly,” says Uniqlo founder Yanai, who grew up in occupied Japan pining for the U.S.A.At the same time, Yanai sees the United States--whose middle class, like Japan's, is a bit woebegone--as a major opportunity for both growth and validation. "America, for me, is the country where, if you have something great to offer, you'll be valued highly," he says. Today, the company has just three U.S. stores, all in Manhattan. Within eight years, Uniqlo intends to have more than 200, bringing in at least $10 billion in stateside revenue. Not only is that more than Uniqlo's current worldwide sales, but it's also about triple the revenue of the current American market leader, Gap, with its 900-plus stores.

Put another way, Tadashi Yanai is very, very hungry.

Yanai has been an Ameriphile for as long as he can remember. Born in 1949 during the U.S. occupation of Japan in the wake of World War II, American culture was omnipresent--and irresistible to a kid. "Democracy, that pioneer spirit. I was very much interested in that," he says. He loved watching Father Knows Best and Route 66. "These families were very prosperous. They all had new appliances and good cars. In Japan, we didn't have any of that, so I thought the U.S. must be a wonderful country."

In 1967, Yanai, then 18, visited the U.S. for the first time. "I didn't think it was a Great Society," he says wryly. He bounced from San Francisco to L.A. to Phoenix to Houston by Greyhound, staying in "cheap hotels where there were holdups and robberies. Then I went to Mexico and I felt so safe!"

None of this dented his love for the U.S., as evidenced by the framed black-and-white photographs of Americana on his office walls. Hanging closest to his desk, there's a 1940 Weegee image of a Coney Island crowd. "Look at this huge number of people," he says, marvel edging into his voice. "I think of them as people who just arrived." Where I see a picture of folks enjoying sun and sand, he reads it as an immigrant story. "You feel the sense of energy," he says, "of those who are crying to take advantage of all the new opportunities."

Yanai found his own new opportunities in the family business. In the same year Yanai was born, his father, Hitoshi, opened a suit shop in Yamaguchi, which was a medieval entrepôt and has a long history of openness to outside ideas and culture. As Japan's economy recovered, Hitoshi built a successful chain of 22 stores. In 1984, Tadashi became president and also opened a store in Hiroshima called the Unique Clothing Warehouse.

The name, later shortened to Uniqlo, was unintentionally ironic. Early on, there was almost nothing unique about it--sportswear from Nike, Adidas, and other ubiquitous foreign brands made up much of its stock--but Yanai kept opening stores and adding more store-brand products. As the chain grew, he was able to lower prices by ordering in greater volume. By 1998, there were more than 300 Uniqlos across Japan.

Yanai had long admired such retailers as Marks & Spencer in the U.K., Benetton in Italy, and, of course, Gap in America. Why, he wondered, wasn't there a Japanese equivalent? "He was never afraid to state his dreams, even if they felt a bit too immodest," one confidant says. "This is very not Japanese." He was telling friends, even in the 1990s, that he intended for Uniqlo to be bigger than Gap.

Yanai is as humble as he is ambitious, and unafraid to ask for help. It came in the form of John Jay, a Chinese-American adman who opened Wieden+Kennedy's Tokyo office in the mid-1990s. Uniqlo was Jay's first Japanese client. "I owe John Jay enormously," Yanai says. "He spent a lot of time on our business, talking to us about what kind of DNA we have and what kind of creativity we needed."

“More than trends, consumers need functionality,” says Uniqlo’s design director. “Everything needs an element of fashion, but that’s more like a spice.”Jay, who had worked at Bloomingdale's for more than a decade, first as creative director and then as marketing director, sent several Uniqlo fleeces to New York and asked his colleagues to do street-level research. "They spent two days getting people around SoHo to try on the fleeces," he recalls. "People said, 'Incredible! Luxurious! How lightweight!' Then we asked, 'How much would you pay for it?' And they said, 'This has got to be $50 or $75.' Some even said $100. But that fleece was $19. I showed the video to Mr. Yanai, and I said, 'Here's your future.' "

Uniqlo knew how to make the clothing; it didn't know how to show the shopper what he could do with it. For instance, Jay and his team helped Uniqlo better display men's dress shirts, hanging them and just rolling up the sleeves. "Fairly common for us, but it was eye-opening for them," Jay says. "Rolling up the sleeves insinuated the lifestyle of the people it was intended for. They realized it was a form of storytelling."

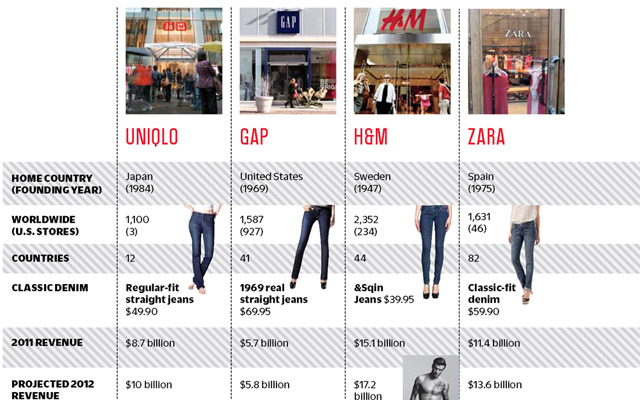

The Global Fashion Fight Uniqlo aspires to be the world’s No. 1 apparel retailer. How the jeans stack up.

With W+K's help, Uniqlo began telling a new story, establishing themes that remain the retailer's branding touchstones. Their first ad together was a full, all-type newspaper page describing Uniqlo's 2,900-yen (then $29) jeans and explaining how it could offer quality denim at that price (massive volume and Chinese manufacturing meets Japanese standards).

Every piece of the subsequent campaign reiterated Uniqlo's commitment to both quality and democracy. A series of spots featuring people from different walks of life proved particularly powerful in socially stratified Japan. "A professor is a much more important person in the eyes of the status quo than a kid. We wanted to flatten that," Jay says. "Each person got 30 seconds. The connector was the product. Giving real people, common people, 30 seconds of very valuable airtime was the most radical thing we did."

Real people, common people, buy things. By 2000, Uniqlo had sold enough fleeces to clothe nearly a third of Japan's populace. Jay's work was so effective that he'd created a conflict with W+K's most prominent client, Nike, which also made highly technical apparel. W+K had to drop Uniqlo, but its work was the booster rocket the Japanese brand needed.

"Yasui."

One brisk, fleece-appropriate April afternoon, I stand outside the rear entrance of Uniqlo's sparkling, month-old, 12-story flagship in Tokyo's luxe Ginza district, interviewing shoppers. My first question for each is the same: What word comes to mind when you think of the Uniqlo brand?

"Yasui."

"Yasui."

"Yasui."

Person after person--28 in a row--uses the same Japanese word, which does not mean "cool." It means "cheap."

Maybe all that advertising worked too well: Uniqlo has never been cool in Japan. But in recent years, the company has added new layers to its brand story to ensure that "cheap," in the Uniqlo context, means affordable, not low quality or déclassé.

To understand how that's sewn into the clothing, I visit Uniqlo design director Naoki Takizawa. "Cool is good, but too cool is bad," he says as we sit in his atelier, a many-windowed, L-shaped space three floors down from Yanai's office. The room is cluttered with rolling racks overstuffed with hundreds of samples and a couple of headless white mannequins wearing tennis outfits. "More than trends, consumers need functionality. The product should be tough. It should be convenient to wear for daily life. Everything does need an element of fashion, but that's more like a spice."

From a nearby rack, Takizawa grabs a fall/winter 2012 parka that's from an unfortunate part of the color spectrum between dark algae and light dirt and that folds into one of its pockets. Its spice is a vertically zipping breast pocket, which echoes a detail seen in the fall/winter 2012 runway shows of Burberry Prorsum and Marc Jacobs. But what's more interesting is the product's evolution. Pointing to a single seam on the left side, he notes, "Two lines is much more complicated to sew. One continuous line is easier. And 20 seconds shorter."

Before Uniqlo, Takizawa was head designer at Issey Miyake, where there was no such thing as too cool. "At Issey Miyake, it was about putting on more and more," he says. "Here, it's about taking away. Cut, cut, cut!" With the parka, Takizawa says that Uniqlo saved 90 seconds through these snips. Multiplied by 600,000 parkas, that's an immense savings of time and money--and it explains how Uniqlo keeps its products yasui. "The only things that stay are the things you need: It has to protect you from the rain, and heat has to escape," Takizawa says. "In some ways, it is the same as what I was doing at Issey Miyake: Both need a high level of design sense. But it's a different kind of design sense."

Uniqlo's distinct sensibility can also be seen through its collaborations with outside designers. Much like its rivals, Uniqlo enjoys both the cachet and the sales boost that can result from high-profile temporary partnerships. In a store full of staples, "our customers need a little bit of news," says Uniqlo U.S.A. CEO Shin Odake. The news this coming fall season are collections from Orla Kiely and Jun Takahashi.

But marketing is only secondary, according to Yuki Katsuta, Uniqlo's senior VP for global research and design. "What we most wanted when we started these collaborations was talent who could give us hints for the future," says Katsuta, who, before Uniqlo, spent 10 years at Bergdorf Goodman. "They wanted to see our boards--really abstract boards--and they wanted to know about our inspiration and our philosophy. That's rare," says Sophie Buhai, who, with Lisa Mayock, designs Vena Cava and did a spring/summer 2011 capsule for Uniqlo. "They appreciate fashion design as if it were spiritual."

"We are not a fashion company," Yanai likes to say. "We are a technology company." He is so fond of this line, he repeats it during each of my three meetings with him. Finally, I ask him what kind of technology he'd like to see on Uniqlo's shelves. He goes wide-eyed and blue-sky on me. "One-size-fits-all clothing," he suggests, thinking of fabric that automatically adapts to the wearer's contours. "Clothes that do not require any laundry. Just rinse it in water, shake it off, and all the dirt is gone." He thinks a moment longer. "Or depending on your mood for the day, maybe fabric where the color may change."

For the moment, Uniqlo's key innovation is a proprietary heat-retaining synthetic material called HeatTech. "People once thought cotton underwear was the best," Yanai says. "Synthetics were only good for mountain climbing or outdoor use, and they were not seen as comfortable." Developed with Toray Industries, HeatTech begins its life in the western Japanese prefecture of Ishikawa, a lovely coastal plain ringed by snow-hatted mountains that is a longtime center for textile innovation. There, in a remarkably versatile factory that also produces carbon fiber for wind-turbine blades and Boeing Dreamliners, Toray makes the polyester-and-nylon yarn that eventually becomes HeatTech long johns, T-shirts, and socks.

The Boeing connection is important: In 1999, Yanai read an article that mentioned Toray was doing R&D for the aircraft titan. "Many people tend to focus on superficial change," he says. "They don't try to tap into essential innovation. If these two companies could get together and come up with something competitive, I thought the same could happen to us."

At the factory, a technician hands me a packet of small white pellets that look like albino peppercorns. These are the seeds of HeatTech. Tidy, massive rows of machines heat the pellets into malleability and spin the stuff into threads that are one-tenth the width of a human hair. Then it's spooled into 64-thread yarn that will be shipped to factories in China. Examine the yarn through a powerful microscope and you'll see a jumble of circles and six-pointed stars. The threads are formed into these two shapes because circles and stars can't fit together perfectly. When spooled, they create air pockets like the ones that make goose-down jackets so warm, helping retain heat and wick away moisture.

The storied Japanese business philosophy of kaizen--roughly, "continuous improvement"--has been applied to HeatTech. From season to season, the improvements can be dramatic. The 2011 yarn has 88 threads, the 2012 just 64--"but it's even warmer!" the worker says.

HeatTech is important on another level: as a symbol of what Yanai values most. A good Uniqlo product, he believes, isn't instantly recognizable like, say, Christian Louboutin's red soles or Ralph Lauren's polo horse. Rather, it totally blends in. HeatTech is meant not to be seen but to be felt. "We have created something that is functional," Yanai says. He smiles. "Perhaps the consumer might want a product like this. Perhaps they might need it."

During the fall/winter 2011 season, the company sold more than 100 million pieces of HeatTech.

Selling sportswear to Americans, says John Jay, "is like selling rice to the Chinese." As Yanai sees it, "The treasure box of clothing--jeans, T-shirts--that all comes from America. But we're giving it a twist." Yanai is, in effect, trying to get the Chinese to like his rice better than their own.

With characteristic ambition, he says, "We want to dominate the market." He also wants to right a previous failure. In 2005, Uniqlo opened three stores in suburban New Jersey malls, only to retreat and retack within a year. "We learned a hard lesson," he says. "Nobody knew about us, and if people don't know what the store is, people will not buy."

Even though Uniqlo has operated a store in Manhattan's SoHo neighborhood since 2006, the company's big American push really began last fall, when it opened a 90,000-square-foot flagship on Fifth Avenue and another megastore on 34th Street, just down the street from Macy's. Those openings came with a months-long, multiplatform advertising tsunami that emphasized the universality of Uniqlo's products. The campaign featured New Yorkers from all walks of life, such as actress Susan Sarandon, Tumblr CEO David Karp, chef David Chang, and soccer player Carlos Mendes. The ads' taglines were quirkily translated and oddly capitalized: "Uniqlo is the ELEMENTS of style." "Uniqlo is clothing in the ABSOLUTE." "Uniqlo MADE FOR ALL." If this push into America fails, it won't be because of obscurity.

Over the next four years, Uniqlo intends to cluster two to three dozen smaller stores around flagships in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. The bundling effect is meant to check distribution costs and maximize local PR buzz and ad spending. This fall, Uniqlo will open its first American mall location since its New Jersey failure--in another New Jersey mall, Westfield Garden State Plaza in Paramus--as well as its first West Coast flagship in a gracious, wide, two-story building built shortly after the 1906 earthquake, just two blocks from San Francisco's Union Square. The location is also across the street from H&M's main local store and two blocks from Gap's hometown flagship. "This is a hotbed of innovation," says Uniqlo U.S.A. COO Yasunobu Kyogoku, insisting that the proximity to Gap is coincidental to Uniqlo coming to the country's technology hub. "It's important for us to be identified with that."

The model roughly replicates what Uniqlo has done in greater China, its largest market outside of Japan. By August, the company will have 175 Chinese stores, radiating outward from the consumer capitals of Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. The big difference, of course, is the economic robustness and growing affluence of China and other emerging markets that Uniqlo is targeting. The company's most recent quarterly report showed that its 70% rise in international sales and the 48% rise in overall profit were almost entirely attributable to China.

Yanai, though, cannot resist the American market. Around the corner from his Tokyo office, there's a large map of Manhattan. There are push pins marking Abercrombie & Fitch, American Eagle, Forever 21, Gap, Hollister, and a half-dozen other brands that could be considered immediate competitors. Significantly, there's one outlier marked: the Apple Store. When I ask Yanai about this, he replies simply, "People have only one wallet."

More notably, Apple is perhaps the best example of a company whose products have become ubiquitous without losing cachet. "Specialness is nice to have," Yanai says, "but what's more important is being made for all."

Uniqlo's success or failure will be decided on the shop floor. So one Wednesday afternoon in April, I go to 666 Fifth Avenue in New York, to work a shift at the world's second-largest Uniqlo store (the Ginza flagship is the biggest). In many ways, the store is a microcosm of Uniqlo as a whole--constantly trying and failing and iterating and readjusting, figuring out what works where.

I am assigned to work with Nicole Chu, an advanced sales associate--"I'm like a baby supervisor," she says--who's part of the team that works the cash registers. In her nine-month Uniqlo career, she has already gotten two promotions and three merit-based raises. "For a lot of Americans, retail is just a stupid job you do to get money," she says. "It's not like that here. I don't want to say it's cultlike, but when I first got here, I was like, 'Whoa, this is intense.' "

Uniqlo prides itself on transparency with the staff. If anything, management overshares, cultivating a sense of shared responsibility. Outside the staff break room, a whiteboard lists sales targets: $9.2 million for April--a middling month--and just north of $150,000 for this weekday. (While Uniqlo won't release sales figures for the U.S. market or for individual stores, a little back-of-the-envelope guesstimation shows that the company would need at least 50 of these massive stores to hit its 2020 revenue targets.)

The culture has Japanese inflections but isn't doctrinaire about it. All associates are trained, for instance, to return your credit card and receipt with both hands, as a sign of respect; one shopper tells me that she appreciates small touches like these. "It's why I come back," she says. "Well, that and the clothes." But floor staff yelling greetings and alerts about the day's specials as they do in Japan? American shoppers complained about being shouted at, and salespeople now share the specials at a decibel level more typical of a slightly deaf grandma.

Chu and I hunt down numerous items, often delving into the stockrooms, which are as disorganized as the shop floor is tidy. Throughout the day, Chu has soothed numerous New York egos without breaking her smile. "I just don't want you to leave disappointed," she says to one especially tetchy shopper who demanded a refund for an item for which she had no receipt. "So sorry for the trouble."

One of the biggest surprises for me has been the diversity of the shoppers. In addition to the tourists--"You can always tell when the school vacations are," Chu tells me--there's a remarkable demographic sweep among the locals. Professionals who work nearby and are grabbing socks and sweaters at the end of their lunch breaks; grandmothers; a stay-at-home dad with his 3-year-old son; a good number of hipsters; a fiftysomething retiree from Florida who says she comes back to New York partly just to shop at Uniqlo.

By closing time, 9 p.m., my feet are aching, every step a reminder that it's been more than a decade since I last worked retail. As the last customers exit, the endless piped-in soundtrack shuts down and an eerie quiet settles over the store. Images from the dozens of Uniqlos I've visited in the last year--in France, the U.K., the U.S., Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan--flash through my mind. Each store was the same yet different. (For some reason, the Hong Kong stores were the messiest.) In each market, Uniqlo has tweaked itself into a fast-growing, fast-mutating microbe intent on insinuating itself into our lives.

Months earlier, when I first met Tadashi Yanai, I'd asked him what makes the quintessential Uniqlo staffer. "First, someone who can adapt," he said without hesitation. "The most serious flaw would be if someone doesn't have the courage to try new things. At least if we fail, we will fail miserably. At least we can say we were bold."

Made For All Advertising Uniqlo’s quirky, consistent images cleverly communicate its everyman, woman--and puppet--appeal.

A 2007 feature from Uniqlo’s magazine was transformed into a successful holiday launch.

Additional reporting by Stephanie Schomer and Maya Uchida

A version of this article appears in the July/August 2012 issue of Fast Company.