Law & Order: Intellectual Property Unit. We're gonna spider, parse, and scan like it's 1998, when Lycos acquired patents that could cost Google hundreds of millions of dollars in royalties.

To understand the patent mess that is gripping Silicon Valley right now, you need to travel across the country to a dark-paneled federal courtroom in Norfolk, Virginia, just down the block from Bob's Gun Shop. That's where lawyers in the I/P Engine vs. AOL suit are taking their best shots in a case about a 14-year-old algorithm that is potentially worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

As I reported in April, I/P Engine claims that Google, along with AOL, Gannett, IAC, and Target--all companies operating or doing business in Virginia, where the suit was filed--are profiting from intellectual property that belongs to I/P Engine. In the late '90s, Andrew Lang and Donald Kosak developed and patented a method to filter and rank the most relevant search results. The patent was later acquired by Lycos, which sold it last year to I/P Engine, which is merging with Vringo (Got all that?). The suit claims that since Google used Lang and Kosak's approach to grow its lucrative ad business, it should pay I/P Engine a royalty for several years of infringement and a licensing fee going forward. Given that advertising makes up the bulk of Google's nearly $38 billion in annual revenue, even a 1 percent fee would be significant.

One major investor in the company bringing the suit is Mark Cuban. Despite being a critic of overzealous suits, Cuban decided to back this lawsuit as a hedge against his other tech-focused investments. But Cuban's not in the courtroom at Monday's pre-trial hearing, where the lawyers from Dickstein Shapiro, a Washington D.C. firm that once won a $500 million infringement settlement, meet the team from Quinn Emanuel, a San Francisco firm that has thwarted previous patent suits against Google.

Together the two sides time-travel back to 1998, the year Google was born.

That's when Lang and Kosak filed for one of the patents--it's also the year Google is born. Back then, Lycos was the 7th most visited site on the Web and one of the most popular search engines, I/P Engine attorneys tell the court. Lycos acquired Lang and Kosak's company that year, and inherited their patents in the process.

This is a Markman hearing, which is like a secret dual between lawyers that the public never sees. Aside from members of the legal teams and a few Vringo executives, the only observers in the stiff-backed pews are investor and hedge fund representatives accompanied by technical advisors whispering the play-by-play. (Vringo's stock, up more than 400% since January, has attracted considerable attention.) The honorable Raymond A. Jackson hears the two sides parse the terminology in the patents and the claims, which can shape the course of the trial. The hearing may not be as overtly dramatic as an episode of Law & Order, but it's captivating because of what's at stake.

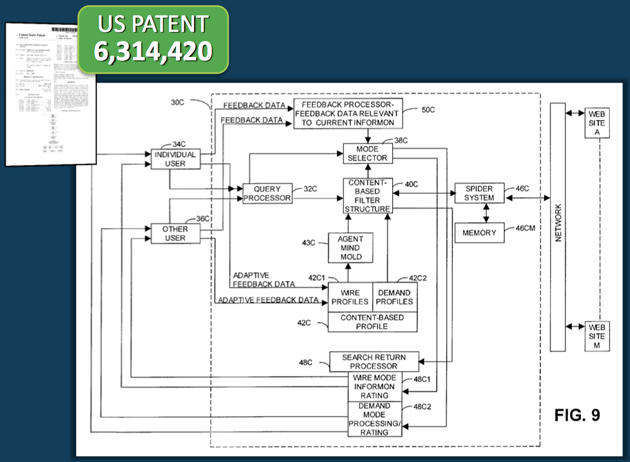

I/P Engine presented this diagram as part of its case.

I/P Engine presented this diagram as part of its case.

The judge tries to simplify the complex concepts--which offer a peek into Google's precious black-box of algorithms that perform the daily miracle of providing answers in milliseconds--so that a jury of non-techies will be able to follow if the case goes to trial as scheduled in October. This isn't easy since the attorneys have an Olympics-level mastery of verbal jujitsu. The debate over the term "scanning" is particularly vigorous. The issue: At the time of their 1998 patent filing, do Lang and Kosak, as the plaintiff attorney suggests, mean the everyday definition, to look for something the way you'd try to spot an umbrella on a crowded beach? Or, as the defense counters, do they use scanning as a synonym for "spidering," a specific function carried out by a search-engine?

"How do you define scanning? For the average Joe Blow with a 12th-grade education?" Judge Jackson asks David Perlson, the lead defense attorney.

Perlson pauses. "I don't know," he says finally, explaining that opposing counsel has just shown a dictionary definition with 12 possible meanings. "It depends," he quips.

It's one word in a case that's already generating thousands of documents, but one interpretation would be broad, the other narrow. One could tilt the case in favor of Google. The other could have a deep impact on its revenue.

Judge Jackson, who made headlines with his recent ruling that a Facebook like isn't protected free speech, seems tough on the defense.

"Why would you be spidering the network?" he asks at another point.

Perlson mulls this over but doesn't answer. The judge repeats the question. Still no reply. Clearly exasperated, he asks a third time. "Why would you be spidering the network? You know what I'm talking about. You're looking for something. Spidering is searching."

Perlson insists on a distinction: "Spidering is a certain kind of search."

It's a tense moment for the Google team, but Markman hearings are hard to read. The hearing comes down to the individual judge. In the coming weeks, Judge Jackson will pore over a transcript of the day and make his ruling on the disputed terms.

The suit is a window into a patent system badly in need of an upgrade. According to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, the number of patent applications increased 61 percent between 1970 and 1990. Between 1991 and last year, applications have increased more than 200 percent. The office is flooded with more than half a million a year, the majority related to information technology. Identifying overlap with earlier patents, or "prior art," is getting increasingly difficult for the PTO as well as CTOs trying to innovate. Not surprisingly, according to the book The Patent Crisis and How the Courts Can Solve It, the rate of suits is nearly twice what it was 20 years ago.

Follow Chuck Salter and Fast Company on Twitter.