Serial entrepreneur Jason Calacanis was on the cusp of big success until Google took it away. So he boldly changed course. The fifth in our Pivot series.

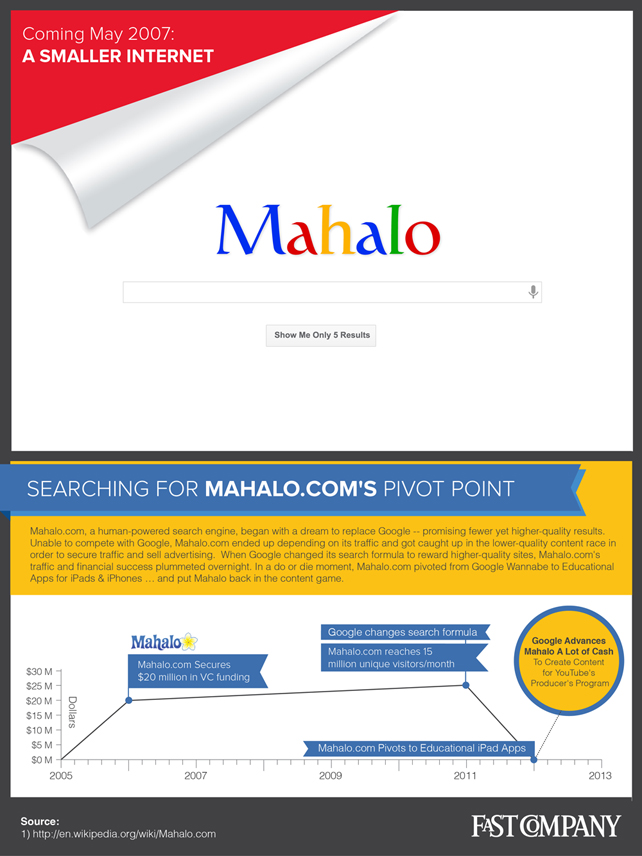

After selling his blog syndicate Weblogs, Inc. for around $20 million and spending a year as an executive at AOL, Jason Calacanis departed corporate life wanting to do something big. The best way to do that, he figured, would be to pick something people use every day, and on the web in 2006 that meant email, instant messaging, or search. He opted for search, since a 1% market share would be worth about a billion dollars.

He envisioned a human-powered search engine that would offer prefab responses to popular search terms and wage war against the machines. This, he believed, would exploit a weakness in Google, which can have a hard time divining what you want. Much of the inspiration came from his wife, who had put together a short, neatly organized email for friends and family with links to places to stay and things to do in Kauai, Hawaii, where they held their wedding. Calacanis wondered why search results couldn't be like that and aimed to compile the top 30%, or about 15,000 of the most oft-googled terms, to skim the cream from the entire search business. Because they would be curated by humans, sifted and sorted and condensed for maximum relevance, users would no longer face 10 million hits, as they are with Google, but just a few dozen.

About This Series

The speed of today's well-funded startups is brutal.

But it does allow for change in direction. This series explores those destiny-altering decisions made by companies that have gone on to great success. Read more about their course corrections--and alternate endings--here.

On paper it sounded clever, and on paper is exactly how he pitched it to potential investors. Calacanis set up a meeting with Michael Moritz of Sequoia, the Menlo Park VC firm, and walked in with printouts for "iPod" and "Kauai vacation" taken from Google, Wikipedia, Yahoo, and a few other sites. He taped them to the wall, where some of them unfurled for 16 pages or more. Next to them, he placed his own single sheet of handmade results. "Which ones are the best?" he asked. It didn’t take long to raise $20 million from Sequoia, Elon Musk, Mark Cuban, and Union Square Ventures.

Calacanis then laid out $11,000 for the Mahalo.com domain name, which at one point had been a nude-celebrity site, hired a team of search compilers, and launched his business in Santa Monica, California. But things didn’t turn out the way he expected. While he was confident his team made search results that were 20% or 30% better, “to get people to switch from a free product to another free product, it has to be a magnitude better,” he says. “Even though there’s zero switching costs, there’s zero reason to switch.”

Infographic: ReadySetRocket

Infographic: ReadySetRocket

Instead of competing with Google, Calacanis found himself dependent on it--and the traffic it funneled to Mahalo. He quickly learned that quality wasn’t the determining factor in search rankings. Instead it was how well a site was optimized for Google’s algorithm and search spiders--the keywords Mahalo used, how many links were coming into it. A cottage industry, led by a Demand Media, popped up around a business model predicated on quantity over quality--churning out as much cheap content as possible. Mahalo also got caught up in this race to the bottom. “This was the most misguided I’ve ever been in my career,” Calacanis says.

For a while it worked, though. Mahalo hit 15 million unique visitors a month and achieved profitability in early 2011. Calacanis was even planning bonuses for staff when suddenly Google changed its search formula in the now the infamous Panda update, which was an attempt by Google to reward higher quality sites. Overnight traffic plummeted, dragging down all of these content farms. (It also hammered the New York Times, which owns About.com, slicing its earnings.) To slow the inevitable burn rate Calacanis immediately laid off half of his staff. He says, “The hardest thing to do is to tell people, ‘Hey, remember the plan I told you? You know where we’re going to change the world? It didn’t work.’ That’s humbling as an entrepreneur.”

Down but not out, Calacanis knew that he would either have to shut down the business or Mahalo had to pivot. After looking at every aspect of the business he realized the answer could be found in popular education videos Mahalo created and posted to YouTube. He decided to enter the education market, but to do that he wouldn’t rely on Google--that had been a fool’s errand--nor would he repeat the advertisement-as-sole-revenue-stream approach, which was not only low margin, it was dangerous. But mobile traffic and video consumption were exploding, and he could turn to Apple’s app store and create high-quality how-to videos for the iPad.

So if you type "Mahalo" into the app store, or "Learn guitar," "Learn Pilates," "Learn a Software Program," or "Learn Hip Hop Dance,” you will find all kinds of courses you can take, ranging from $1.99 to $4.99. Each costs Calacanis around $20,000 to make, and thus far some are doing quite well. The guitar app, for example, has brought in tens of thousands of dollars since it was released, he says. What’s more, his old enemy Google has advanced Mahalo “a very large amount of cash” to create content for YouTube’s "producers" Program.

“We invest probably 50 times the effort that we did in the content farm days,” Calacanis says. “I’m having the time of my life, which I couldn’t say about that period when we were much more successful in terms of revenue and traffic."

He adds: “Even for a seasoned entrepreneur, it’s easy to get drawn off target and start pursuing growth for the sake of growth as opposed to quality.”

But then came the pivot.

Adam L. Penenberg is a journalism professor at NYU and a contributing writer to Fast Company. Follow him on Twitter: @penenberg.

[Image: Flickr user Michael Dawes]