The annual sports stat geek conference held at MIT's Sloan business school is part Star Trek convention, part academic conference, part job fair, part media circus (thanks, ESPN!)--and the future of the $400 billion sports business.

Kirk Goldsberry and his geographic-based shooting analysis scored big at Geekapalooza this year.The crowd, still buzzing from the heady action, heads for the exits on Saturday night. The unlikely star from Harvard looks spent, hair disheveled, shoulders slumped. Everyone in the sports world suddenly wants a piece of him: NBA teams, the media, fans who stop to shower him with congrats. Kirk Goldsberry doesn't actually play basketball--he's a visiting scholar with a PhD in geography--but at the recent MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference in Boston he's nonetheless having a Jeremy Lin moment.

Kirk Goldsberry and his geographic-based shooting analysis scored big at Geekapalooza this year.The crowd, still buzzing from the heady action, heads for the exits on Saturday night. The unlikely star from Harvard looks spent, hair disheveled, shoulders slumped. Everyone in the sports world suddenly wants a piece of him: NBA teams, the media, fans who stop to shower him with congrats. Kirk Goldsberry doesn't actually play basketball--he's a visiting scholar with a PhD in geography--but at the recent MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference in Boston he's nonetheless having a Jeremy Lin moment.

Ordinarily, Goldsberry does health care research. He creates maps that reveal a community's lack of access to fresh produce, and he publishes his findings in academic publications such as the Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition. But it's Goldsberry's latest research paper--"CourtVision: New Visual and Spatial Analytics for the NBA"--that has thrust him into the sports geek limelight. "I woke up yesterday never having been on national TV or in The New York Times and Sports Illustrated or interviewed by the Wall Street Journal," he says, incredulous that all those things have since happened.

This is the Age of Data, when smart companies gather and interpret every possible scrap of information about every aspect of their business in hopes of gaining a competitive advantage. Sports, always awash in statistics, has become a fascinating crucible for how analytics can transform an industry. Teams, particularly those in pro baseball and basketball, are focused on using numbers to improve player evaluations and game strategies. They're hiring PhD-level statisticians. They're assembling teams of analysts, an alternative-universe version of their on-court team. And in the case of the defending NBA champion Dallas Mavericks, they're even putting one of these modern-day mathletes on the bench to offer input during a game.

As in other industries, they're constantly debating which stats matter and when human judgment should supersede data. "Statistics are like a lamp post to a drunk," Toronto Maple Leafs GM Brian Burke tells the crowd at one point, "useful for support but not for illumination."

Grantland founder Bill Simmons signing a new compilation for the countless Simmonsians on hand.

Grantland founder Bill Simmons signing a new compilation for the countless Simmonsians on hand.

The Sloan sports analytics conference, dubbed Geekapalooza by Dallas owner and regular attendee Mark Cuban and Dorkapalooza by ESPN columnist, podcaster, and ubiquitous panel moderator Bill Simmons, is ground zero for the sports world's evolving relationship with analytics. Held the first weekend of March at the downtown Hynes Convention Center, the sold-out event drew more than 2,200 people, up from 1,500 last year. Officials from the major sports leagues are here, as are team owners and executives from 73 pro and college teams as well as representatives from a Who's Who of corporate America, including the usual suspects (Nike, CAA, and Ticketmaster) and some not so usual ones such as Facebook, Goldman Sachs, and IBM. Nearly a third of the crowd consists of students, from 175 schools, including the country's top business schools.

The first conference, six years ago, was small enough to be mistaken for a class at MIT's Sloan School of Management, with just 60 people. Now ESPN, the lead sponsor, brings in more than that many staffers, nearly 100 this year, to use its promotional muscle and savvy to turn an event where much of the action involves presenting academic papers into a high-profile, entertaining affair. It films an episode of its Numbers Never Lie show live at the conference, devotes the latest issue of ESPN the Magazine to analytics, and cranks out podcasts and short videos online.

This isn't the ESPYs by any stretch. When the talk here turns to models, they're talking about the mathematical variety. But for those who aren't athletes and love endlessly dissecting sports, the gathering is divine.

***

[Left: Like baseball players and sunflower seeds, statheads and mind-bending research are inseparable at the conference.]

[Left: Like baseball players and sunflower seeds, statheads and mind-bending research are inseparable at the conference.]

You don't need a math degree to grasp that the odds of a team sharing its know-how here are low. Even those execs appearing on the promising "Basketball Analytics" panel. "The key is talking without giving anything away," Boston Celtics assistant general manager Mike Zarren admits on stage.

Just the same, there's plenty of fishing. Throughout the day on Friday, execs scout the research displayed on easels lining the corridor. "You try to find the loose-lipped guy," says Ben Alamar, a PhD economist who consults for the Oklahoma City Thunder from Silicon Valley, where he's the founder of Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports and teaches at Menlo College. "There's a lot of 'Did you see that paper? What'd you think?'"

It's impossible to tell what Alamar thinks. "Academics have great tools," he says, "but they don't think like GMs or coaches." It's the sort of cryptic comment that suggests he's either dismissing the easel in front of him or offering a red herring to throw other teams off.

Okay, fine. So what exactly does Alamar consult on for the Thunder? "I can't say," he says with a smile.

Even so, his analysis influences specific transactions, right? Another grin. "I'm not allowed to talk about it," he says.

Later, Tom Tippett, head of analytics for the Boston Red Sox, is studying research on another easel, "Deconstructing the Rebound with Optical Tracking Data." "I want to see what might apply," he says. Computer-vision cameras in a handful of NBA venues gathered the data, a system similar to what will soon be installed in baseball stadiums. "Most of the time we only work to understand what has happened, to know the players' skills, not the effect of their opponents or the environment," Tippett says. "But when you're working for a team, it's all about predicting what's next. How do you change the arc of a player's career?"

So numbers that change what a pitcher throws in a game or maybe prevent an injury before it happens. That sort of thing?

Tippett's eyebrows arch, but his lips are sealed.

***

[Left: Goldsberry analyzed not just the result but the locastion of every field goal attempt over five years to identify the NBA's best shooters.]

[Left: Goldsberry analyzed not just the result but the locastion of every field goal attempt over five years to identify the NBA's best shooters.]

The Sloan event began really as a conversation between friends. Jessica Gelman and Daryl Morey, both sports nuts and former consultants, both with Ivy League MBAs, would get together and talk about the future of the industry. Gelman, who had a stellar basketball career at Harvard and played professionally in Europe, worked for the Kraft Sports Group, which owns the Patriots. Morey, now general manager of the Houston Rockets, was senior vice president of operations and information for the Celtics. A computer science major and avid reader of sports stats pioneer Bill James, he was eager to introduce more advanced data analysis to the NBA. At Sloan, where Morey earned his MBA, the two taught a six-week course, bringing in sports executives to share their experiences. "He was doing the team side, and I was doing more the business side," says Gelman, vice president of customer marketing and strategy at Kraft.

In 2006, the Rockets disrupted Gelman and Morey's plans to develop a semester-length course by hiring him as assistant general manager, a shocker around the league and a huge validation for his data-driven approach. A year later, at just 35, Morey was promoted to GM. Meanwhile, he and Gelman turned their class into an annual conference. In the wake of Michael Lewis' bestseller Moneyball, the industry's appetite for new data and fresh thinking was huge. The second year, the GMs of the four reigning championship teams shared the stage at Sloan (five champions are represented this year, including Manchester United). Then nerd darlings Michael Lewis and Malcolm Gladwell came. ESPN got involved. And Cuban became a regular, sitting in on the academic research presentations.

The agenda keeps expanding. This year, MIT Sloan Sports includes sessions on the effectiveness of sponsorships and the importance of "fanalytics," data on fan behavior, to drive ticket sales and better pricing. There are trade show booths down the hall from the research papers. The Vitamin Shoppe tries to convince teams, including the Milwaukee Brewers, that its protein shakes fuel athletes to put up good stats--legally, they emphasize (good to know if you're the Brewers given the Ryan Braun controversy). Edge 10, a software company from England, charts health-related data on athletes. (The red icon indicates a bad day--"Maybe he had a niggle," says Edge10's Richard Dry, using a Harry Potter-sounding term for a slight injury.) TeamRankings promotes "Stat Geek Idol," its March Madness competition for sports analysts judged by Cuban, Morey, Groupon chief data officer Mark Johnson, and other data heavyweights.

The conference shows how pervasive data has become in sports and where the gaps still remain. "It's hard to get reliable data on college football," bemoans Eddie Pettis, a Google tech manager by day and co-author of the football blog Tempo Free Gridiron. "Baseball has a large advantage." Which is part of the draw, though, to be a pioneer, the Bill James of another sport.

Until this year, MIT Sloan Sports hadn't conducted a panel on tennis analytics. Listening to Roger Federer's coach Paul Annacone, former top-five player Todd Martin, and Craig O'Shannessy, a pro coach and founder of the strategy site TheBrainGame, you can understand why. "There's no shared service," says Martin. "This isn't a team sport with a $500,000 budget for analytics."

True, but the feet-dragging doesn't make sense to O'Shannessy, who routinely tapes matches to tag rallies and scour the results for strategic clues. Analytics, he says, "should be a strength of our game. Tennis is a game of patterns." Patterns such as Federer's serve, which according to O'Shannessy, are 50% are wide to the forehand side.

Stats icon Bill James (right) appearing on ESPN's Number Never Lie with co-host Michael Smith.

Stats icon Bill James (right) appearing on ESPN's Number Never Lie with co-host Michael Smith.

If Annacone is squirming at that nugget getting out, he doesn't let on. Data, he suggests, has its limits. Once, while coaching 14-time grand-slam event winner Pete Sampras before a match, he mentioned how an opponent had served eight break points to Sampras' backhand. That day, the player did the exact opposite. "Pete said, 'Guys have tendencies, but we're the best players,'" Annacone recalls. " 'We can change them.'"

O'Shannessy is undeterred. "I've been beating on the door of USTA for years," he says. "It takes time."

***

"This conference is the culmination of 30 years of my work," Bill James tells a packed house on Friday afternoon. He's on stage with Simmons for a little one-on-one chat, the old guard and the new, which the nerd faithful have been waiting for.

James is tall, with a full, gray Hemingwayesque beard, a dark suit, and a lumbering gait. He looks imposing, not someone you'd approach, until you get close enough to see that the designs on his tie are characters from The Simpsons. And everyone seems to get close over the two-day event. He can't walk very far in the convention center without someone stopping him to say, "I read your books growing up" or "You're the reason I got into stats." Everyone's a student of his, from team execs to 12-year-old Jackson Kelley of Boston, escorted by his mother. Simmons introduces James as "the godfather of stats."

Today, it's hard to grasp how modestly the modern era of sports analytics began. Before the launch of ESPN or sports fantasy leagues or even computers for that matter, James, a former English teacher, pored over baseball box scores and scribbled charts by hand at a pork and beans factory in Lawrence, Kansas. When he wasn't checking the boiler, he was developing unconventional stats to assess the performance of players. Baseball wouldn't give him the time of day.

"I was challenging the way that people thought about the game," he says. "Here's some guy working in a factory in Kansas saying, you don't know what you're talking about." Taking on something as established as baseball was akin to taking on religion. "Religion is elaborate and intricate," he says. "It fills in all the boxes with the philosophy and wisdom of teachers who went before us. It's complicated, and it heals itself. For that reason, it's much harder to change how people think. When people point out a gap, something fills it in. It's a living interactive system of thought."

But James got through. "I always believed when in an argument it's immensely powerful to have the facts on your side," he says. He created sabermetrics, a stats-intensive study of baseball and published more than two dozen "Baseball Abstracts" books. In 2003, one of his former readers, Red Sox owner John Henry, hired him. James, who received World Series rings for Boston's 2004 and 2007 championships, still works for the team as a consultant.

Goldsberry making his national TV debut on ESPN.

Goldsberry making his national TV debut on ESPN.

Today, blue-chip prospects like Goldsberry (one of the day's guests on Numbers Never Lie) find themselves in demand at the Sloan conference if they dig up a new insight or a new statistical measure. Goldsberry's has the nerd-friendly moniker, "Range %." "I'm the kind of guy who looks at a player who takes a shot from 18 feet and asks, 'Was that a good shot or a bad shot?'" he says. "That's the question you're always trying to understand."

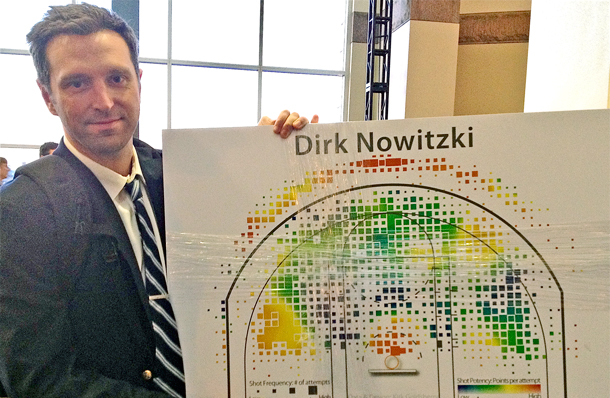

He turned to the data, every field goal attempt--more than 700,000--in every NBA game played between 2006 and 2011. What gets overlooked in evaluating shooting, he says, is where the shots are taken. So he divided the court into 1,284 possible "shooting cells," adding a layer of geographic information, his specialty, to the conventional measure, the percentage of shots a player makes. Someone who shoots well from more areas of the court, Goldsberry reasons, has better range and is more effective than an accurate but predictable shooter rooted to fewer spots on the court. The league's best shooter, then, isn't high-scoring young gun Kevin Durant or LeBron James. It's the Phoenix Suns' ageless point guard (truth be told, he's 38, but you'd never know it) Steve Nash.

Saturday, as the event winds down, a high school student from the New York prep school Horace Mann stops Goldsberry and gushes, "I read your paper!" This being a stats conference and not a sporting event, an autograph won't do. The kid wants the poster-board showing five years of shots taken by the Mavericks' Dirk Nowitzki (the league's fourth best shooter, according to Goldsberry).

"I'll buy it," the student offers.

"Sorry," Goldsberry tells him.

He's hoping to catch the eye of Cuban, the NBA's patron saint of sports analytics. A few minutes earlier, in the last session with Simmons, the Mavs' owner offered a glimpse inside his stats-intensive operation, where director of basketball analytics Roland Beech, the founder of the stats site 82games and the first stat geek to earn a championship ring, sits alongside the coaches during games, four staffers log live game data (Cuban wouldn't say what), and the next frontier in data is "influencing the numbers," he says. "Psychology."

Holding the Nowitzki chart like an airport limousine driver, Goldsberry positions himself outside the hall. Soon enough, Cuban is heading his way. But he's flanked so closely by another researcher pitching his idea that Cuban doesn't seem to notice.

Disappointed, Goldsberry gathers his things. By the escalator, he gets a second chance. Cuban is waylaid by another researcher. When he's through, Goldsberry steps in for his Shark Tank moment. He holds up the chart. Cuban's eyes light up. "I saw that!" he says.

After a few minutes, Cuban leaves with the business card Goldsberry had printed up for the conference, featuring miniature color-coded shot charts on the back. It's a small, clever touch. Who knows, it might just increase his odds.

[Ed note: How analytic is the event? No sooner had it ended than this tabulation of tweet traffic made the rounds.]

Follow Chuck Salter or Fast Company on Twitter.

Read more about March Madness and the rise of data in sports:

Who (Or What's) Best At Predicting March Madness Winners?

NumberFire: "Moneyball" For Fantasy Leagues