Social media has a lot to say about T.V. Can Bluefin cash in on that?

Deb Roy created Bluefin's business plan with an MIT colleague in 48 hours. | Photo by Brad Dececco

Deb Roy created Bluefin's business plan with an MIT colleague in 48 hours. | Photo by Brad Dececco

Bluefin Labs sits on the periphery of MIT's Cambridge, Massachusetts, campus, in a former hose factory located next to a movie theater. But the company really exists at the virtual intersection of social media and television. Consider, for instance, what a tweet can tell us about a new TV show. Actually, consider what thousands of tweets can tell us about New Girl, a Fox sitcom starring Zooey Deschanel. To analyze how social media relates to a particular show, Bluefin processes about 1,389 hours of television a day and more than 166.7 million comments; on a recent evening, its servers located 15,433 comments that included something about New Girl. Using special algorithms, the company's computers determined (among other things) that viewers of the show also like to talk about ABC's Suburgatory. Information like that can be valuable to networks and advertisers, so it gets packaged into the company's new product, Bluefin Signals, which now has more than 25 customers, including CBS. Bluefin, claims CEO Deb Roy, has developed what he calls "a real-time switchboard connecting TV with the social web."

Bluefin Labs sits on the periphery of MIT's Cambridge, Massachusetts, campus, in a former hose factory located next to a movie theater. But the company really exists at the virtual intersection of social media and television. Consider, for instance, what a tweet can tell us about a new TV show. Actually, consider what thousands of tweets can tell us about New Girl, a Fox sitcom starring Zooey Deschanel. To analyze how social media relates to a particular show, Bluefin processes about 1,389 hours of television a day and more than 166.7 million comments; on a recent evening, its servers located 15,433 comments that included something about New Girl. Using special algorithms, the company's computers determined (among other things) that viewers of the show also like to talk about ABC's Suburgatory. Information like that can be valuable to networks and advertisers, so it gets packaged into the company's new product, Bluefin Signals, which now has more than 25 customers, including CBS. Bluefin, claims CEO Deb Roy, has developed what he calls "a real-time switchboard connecting TV with the social web."

The key to Bluefin's technology is the ability to map the "tv genome." Here, all the social-media comments hover above all the tv content at a given time. Bluefin's algorithms connect the language of the comments to their context--what's on tv. Taken together, those connections create a feedback loop between viewers and content, revealing how people are reacting to what they're watching in real time.

[twistage cda8de53484b5]Bluefin links social media comments to tv by filtering all incoming comments through a "video fingerprint" of the shows and commercials currently airing.

Roy has been trying to use big-data computing to explore the connections among images, language, and meaning for most of his professional life. As a media arts and sciences professor at MIT, he created algorithms that link words to visual context and used them, along with 240,000 hours of home video and audio, to analyze when--and where--his infant son learned to talk. Michael Fleischman, Bluefin's cofounder and now CTO, and at the time Roy's PhD student, applied similar techniques to teach computers to link on-screen action to verbal descriptions in major-league baseball games. The National Science Foundation was impressed with the work. "One of the managers from the NSF's Small Business Innovation Research program called me up,'" Roy recalls. "I said, 'You've got the wrong guy--I don't have a small business.'" But he and Fleischman applied to the program, were accepted, and found they had 48 hours to create a company. In the rush, they chose the name Bluefin, a sushi restaurant they frequented. In addition to $1.15 million from the NSF, they got $1.2 million from angel investors and $6 million from Redpoint Ventures. Next year, Roy says, the company will seek more funding.

They are wading into rough waters. Nielsen, the media measurement company, has a near monopoly on television data; its research remains the standard when it comes to the question of where to put ad dollars. "We're looking for Bluefin to add something new," says CBS chief research officer David Poltrack, who is intrigued by the product. If it turns out that Bluefin is just confirming something CBS already knows, Poltrack adds, "it's not something we need."

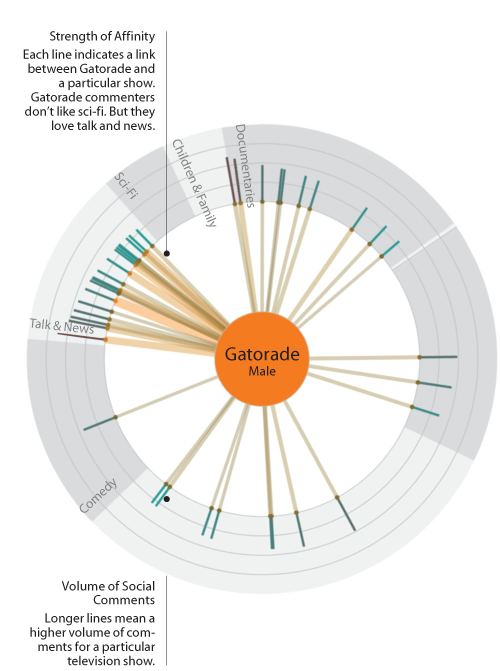

But Roy doesn't think Bluefin is competing against Nielsen, nor does he think it's competing against Twitter, which already supplies networks with data but only captures one facet of social media. Roy says his company offers something different. How many people tune in is important, he admits. But such numbers can't give advertisers or networks the granular information revealed by his computers. What's more, Bluefin can mine connections among shows, social media, and advertisements. For instance, this summer, Diet Pepsi studied audience reactions to an advertisement starring Modern Family's Sofia Vergara. During the airings of the ad, social-media comments about Diet Pepsi increased about 19%. Bluefin collected data from 1.8 million people who commented on TV shows on which the ad played. Then they discerned "affinities" by finding out how many commenters were saying something about each show and Diet Pepsi. Understanding these affinities gives Diet Pepsi something valuable for the future: Directing more ad dollars to the commenters' favored shows may prove far more efficient.

For a Chevy Cruze ad, meanwhile, Bluefin generated a cloud of common words gleaned from social-media responses. In the ad, a man kisses a woman goodbye, drives off, and asks his car to read his Facebook news feed, which reports the woman's latest status update: "Best first date ever." He smiles. But the audience, Bluefin discovered, did not. Crash and WTF were popular, according to the cloud, and Chevy was only the third most-mentioned word--coming in after car and Facebook. Overall, 58% of the comments were negative.

Bluefin does have limitations. For one thing, it's sometimes tough for a machine to understand the ambiguous language of social media. Already, Bluefin's algorithms are refined enough to distinguish that the word coke in Two and a Half Men comments is not referring to the soft drink but to Charlie Sheen's reported vice. But a harder challenge involves the analysis of human sentiments. As Fleischman explains, "People often talk about things in much more fine-grain ways than positive or negative--they love to hate a character, they're sarcastic, that type of thing." It's easy for humans to discern the difference between expressions of happiness and anger, in other words. But not so for computers.

That may soon change. Roy's algorithms have the ability to fine-tune themselves, learning what he calls "the language of television" by employing machine-learning techniques. For instance, his algorithms have uncovered differing emoticon styles. A simple :) will signify a commenter who is, on average, 10 years younger than one who writes :-). Such small nuances give comments additional meaning and value.

But value for whom? Isn't it good only for the people selling us stuff? "This isn't social television--this is social advertising," says Nancy Baym, a professor of communication studies at the University of Kansas. "This is about turning the audience into marketers." Roy doesn't buy it. "TV is not just used for advertising," he says. And regardless, he adds, if given a way to figure out what audiences want, advertisers will waste less of our time. "I'd much rather have an attuned marketer who understands if I care than one who's just pushing TV spam at me."

For Roy, though, that argument is more about business than pleasure. His company's databanks contain any show he could ever want to watch--but there's no time. These days, he admits, he just doesn't watch much TV.

Media And The MessageWith a trove of big data--5 billion online comments and 2.5 million minutes of TV per month--Bluefin charts the complex relationship of male TV viewers to Gatorade.

A version of this article appears in the December 2011/January 2012 issue of Fast Company.