Ursula Burns wants to remake her firm into the company American business can’t live without. But can Xerox succeed in a world without Xeroxing?

Burns is the first African-American woman to lead a U.S. company of Xerox's size and influence. | Photo by Jake Chessum. Makeup by Oslyn Holder for Epiphany Agency

Burns is the first African-American woman to lead a U.S. company of Xerox's size and influence. | Photo by Jake Chessum. Makeup by Oslyn Holder for Epiphany Agency

After eight meetings with the President of the United States, Ursula Burns still wonders what the button is for. "These meetings are all very choreographed, very much according to protocol," she says. "That usually isn't my thing, protocol." She is telling me about her latest encounter, a hastily called meeting at the White House this past August, during the height of the debt-ceiling debates, to discuss methods for spurring the economy. She and seven other CEOs, among them the heads of American Express, Johnson & Johnson, U.S. Steel, and Wells Fargo, were placed like pegs in a tightly designed game board, sitting in front of tent cards with their names in a formal script, waiting for the President to arrive. At the President's place sat a folio of notes and a small box with a red button. Burns, who had been seated in a position of honor to Obama's right, was to be the last to speak. As she waited, she considered whether the button could be the executive branch equivalent of The Gong Show gong. She thought to herself: Maybe he pushes it if he doesn't like what we say.

When it was her turn, Burns recalls, the President said, "'This has been really good, and now I'm bracing for the tough one.''' Burns smiles at the recollection.

She is known to be tough. Burns is the first African-American woman to lead a company the size of Xerox, coming to power in 2009 during an economic tailspin that continues to threaten the global economy and her company's bottom line. She is the second woman to run the iconic firm, in a historic succession that has produced historic results: Working closely with friend and former CEO Anne Mulcahy, Burns was part of a small group of executives who rescued Xerox from near bankruptcy in 2001 and began moving the company away from its machine-making roots and into a different business entirely. "The thing I valued most about Ursula, and why I valued her participation in senior management, is that she has the courage to tell you the truth in ugly times," says Mulcahy.

Being direct is her calling card. When Burns talked to Obama about leadership and the practical aspects of what big business needs, it was serious advice, respectfully offered.

Burns isn't nostalgic. She has no desire to dwell on Xerox's former glories. Instead, she is willing to do whatever it takes to reposition her firm for an era of technological upheaval.She did, however, tell him that he owed her $3 billion. The debt-ceiling crisis had played havoc with the valuations of many American firms, including Xerox's. Had Obama seen its share price lately? Wasn't he at least partly responsible? "What did I do?" Burns asked him. "All I did was wake up and my share price is down!" The remark elicited a laugh from the President, who is also, by way of the federal government, a major Xerox customer. It was, in many ways, a signature move. Burns, not a protocol kind of person, is always willing to push the button herself.

"I'm a black lady from the Lower East Side of New York," Ursula Burns says. "Not a lot intimidates me." Burns grew up in the projects on Delancey Street, close to all the trouble that a poor kid can get into in a city in decline. Her mother, Olga, who died in 1983, washed and ironed clothes for money; she also knew her way around a deal--she traded cleaning services to a neighborhood doctor in exchange for health care for her three kids. Ursula, the middle child, says of her father, "He wasn't in the picture." Burns describes her mother as supremely confident and someone who expected great things from her kids. "I don't want to overemphasize this," she says, "but not a day goes by when I don't think about my mother and what she would think about what I just did. I often adjust my approach."

Back in the Old Neighborhood: Ursula Burns, pointing to her childhood home in Manhattan. | Photos by Jake Chessum

Back in the Old Neighborhood: Ursula Burns, pointing to her childhood home in Manhattan. | Photos by Jake Chessum In many respects, Burns's ascent to the top of Xerox--and the decisions she's been willing to make to ensure the company has a future--carries a business lesson for uncertain times. She is, by her own admission, in love with the company that gave her a livelihood and a 31-year career. And yet she isn't the least bit nostalgic when the conversation turns to returning Xerox to its former glories. That was then. She has long been willing to do whatever it takes--dismantle the company's manufacturing unit that shaped her career; cut back or eliminate products that once defined the Xerox brand; branch out into uncertain (and risky) new areas of business--in an effort to reposition the company in an era of technological upheaval. What's more, unlike her contemporaries at, say, Hewlett-Packard, Burns's career turn demonstrates that you don't need an outsider to save the day. An insider can do it just as well--and can bring with her an incomparable institutional knowledge and the deep well of respect of her peers. "I came in the wrong way," says Mulcahy of her surprise ascent to CEO. "As difficult as it was, Ursula came in the right way."

Burns had an early aptitude for math that earned her a scholarship to the Polytechnic Institute of New York and a degree in mechanical engineering in 1980. She was tapped for a summer engineering internship at Xerox, and she never fully left. The next year, she earned a master's from Columbia that Xerox helped pay for. "I saw what was possible for myself early," she says. During a 1989 "caucus"--a type of employee gathering organized around work-life topics--a question was asked about Xerox's diversity initiatives, and whether they lowered hiring standards. Wayland Hicks, the president of marketing and customer operations, weighed in. As he politely explained why the company did not lower standards, Burns pricked up her ears. She thought, Why give the question the dignity of a response? She raised her hand. "We had a little debate about it in front of the room," she says. "Why not attack the assertion directly?"

Hicks later coached Burns on the finer points of corporate diplomacy. But he was impressed by her guts and intelligence. Not long after, Hicks tapped her as his executive assistant, a job that served as a de facto leadership-training program. "That was the first sign she was really on the executive track," says Mulcahy. "It was a significant signal to everyone." By 1991, her outspokenness and keen business insights had gained the attention of then-CEO Paul Allaire, who poached her from Hicks for a similar position in his office. By 1997, she was the vice president for worldwide manufacturing and had led the push into color copying. Soon, there wasn't a manufacturing job she hadn't touched or a Xerox product she didn't understand.

Shadowing her from the sales side was Mulcahy, whom she considers a close friend. "Our careers grew the same way from different directions," says Burns. "If she did it, I did it next. She was always one step ahead of me." Both women are Xerox lifers; both married "Xerox husbands," says Burns. (Burns's husband, Lloyd Bean, is now a retired Xerox scientist.) As Burns puts it: "Xerox sucks you in and you become part of each other."

Still, by the late 1990s, Mulcahy and Burns were mostly part of a dying company. Xerox was sputtering in the face of Japanese competition. At the same time, the digital world's ascendance over Xerox's empire of paper, and paper copiers, seemed inevitable. A new CEO, a former IBM'er named G. Richard Thoman, was appointed in 1999. He lasted about 13 months. By the time the board asked him to leave, the company's stock had plummeted from a record of nearly $64 a share in May 1999 to $27 in May 2000, and Xerox was heavily in debt. Jim Firestone, currently the president of corporate operations, says it simply: "We broke. The company broke." Burns is characteristically direct. "We had lost complete faith in the leadership of the company," she says. "We didn't have any cash and few prospects for making any." And that wasn't the worst part. "The one thing you wanted was good and strong leaders that were aligned and could get us through things and we didn't have that."

By 2000, Burns was ready to leave. But when Mulcahy became CEO, she helped persuade Burns to stay. And it then fell to Burns to outsource Xerox's manufacturing. The move was crucial to Xerox's cost-saving efforts; if done wrong, however, it would cripple Xerox's relationship with its customers. Burns chose the global manufacturer Flextronics, but to complete the deal, she needed the support of the Xerox union, some 4,000 employees in a facility near Rochester. Burns recalls: "I told them the truth, in as much detail as I could, about what was happening." Says Mulcahy: "She literally convinced the union that it was going to be either some jobs or no jobs. For anyone. It was survival. There was no other way." By 2004, Xerox had returned to profitability. But the company had dropped from 100,000 to 55,000 employees in less than four years. What's more, the bigger issue still remained. "What we had to do was step back and think," Burns recalls. "What is it that Xerox really does?"

What Burns remembers most about her first day as the CEO of Xerox was dinner the night before. Over a meal with Mulcahy, she got the news that she had been hoping for. "We were pushing to take the company in a direction that made a lot of sense--on paper," she says. The direction she was referring to was the acquisition of Affiliated Computer Services, or ACS, a company that had started as a family-owned data-entry business in the mid-1980s and had grown into a $6 billion services powerhouse with a foot in the door of seemingly every back office around the world. If you paid a toll or a parking ticket, applied for a credit card, or went to the doctor in America sometime in the past year, chances are ACS worked your paper trail behind the scenes.

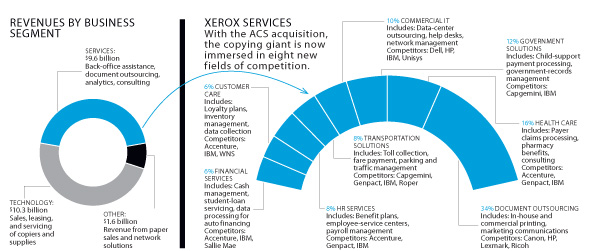

Where Does Xerox's Revenue Come From?The enterprise giant takes in nearly $22 billion a year. Here's how.

By the time Burns started courting ACS, Xerox had already taken tentative steps into the business processing sector, clearly aware that copiers and faxes were not going to keep them afloat in a digital world. The company had started by buying two small firms in 2007--one that streamlined the electronic discovery process for litigation and one for mortgage documentation. "We were being dragged by our customers into managing large, complex business processes for them," says Burns. But cobbling together small acquisitions into a bigger business wasn't going to cut it, Burns concluded, with competitors like IBM targeting some of the same lines of business. Acquiring ACS would double Xerox's size and beef up what the company earned from services to nearly half its annual revenue. Lynn Blodgett, CEO of ACS, had been fielding offers from Xerox competitors and private-equity groups. But in 2009, he gave Burns and Mulcahy a formal nod over dinner. The final deal, announced some 90 days later, was met with skepticism from Wall Street. From that vantage point, it seemed like just another detour in Xerox's long road to irrelevance.

Burns tells this story after a long day of presentations at an analyst meeting held at Citi Field--Xerox does the back-office work for the New York Mets--the day after her 52nd birthday. It happened to be some eight months after the ACS acquisition (the deal was finalized in February 2010), and Burns was feeling optimistic. Her day had been filled with big talk and PowerPoint presentations--visions of Xerox-ACS synergies and workflow diagrams and product demos. Her essential argument, however, was this: Business services was a smart area to work in, with dependable income even in bad times. By Burns's calculations, it was a potential "$500 billion marketplace." And Xerox's advantages in getting a large slice of that pie lay in its innovative capabilities.

For four decades, the company's research facility--Xerox PARC, in Palo Alto--had shown its worth in creating not only the laser printer and ethernet cable, but the graphic user interface that Steve Jobs encountered in late 1979 and discerned to be the future of personal technology. In 2010, Xerox research was not focused on improving the PC. But it was focused on making any process that a business or government needed wildly more efficient. Sure, clients didn't value copiers quite so much anymore. But they hadn't yet seen how Xerox machines had learned to read and understand the documents they scanned--and how work that might take a room full of paralegals, toll collectors, or mortgage processors a week could now be rendered in minutes or, perhaps, seconds.

In a world that's currently dazzled by social graphs and app releases, Burns acknowledges that business services can sound decidedly unsexy. "These are processes that a company needs to run their business," she explains. "They do it as a sideline; it's not their main thing. They don't major in it." Her point is that Xerox does do it as a main thing. Anyone at Xerox is quick to assert they work just as hard as other big tech companies to change the way the world is wired. Burns simply believes that the direction she is taking the company will preserve Xerox's legacy as innovators and continue the firm's growth.

She has reasons to believe this. Some of them relate to Xerox PARC's work. Some reside within a chateau that houses the Xerox Research Centre Europe near Grenoble in the French Alps. Burns sent me on a pilgrimage there--she did the same for ACS's Blodgett, when the two began talking about merging--because it is the best way for her to make the case that while Xerox was struggling to stay relevant between 1995 and 2010, it was doing a ton of stuff right, too.

The center was founded in 1993 to help Xerox prepare for a future when its technology products (printers and paper copiers) became a commodity, and when business services (to help Xerox customers work faster and cheaper) would be the way forward. "We were a document company at the beginning and it was very important to figure out how we could extract what was in the documents to automate certain things," says Monica Beltrametti, a PhD in theoretical physics and the founding director of the center.

Under Beltrametti's watch, Xerox machines have increasingly learned to understand languages, analyze photos, and route data in a fraction of the time that it takes error-prone humans. A machine in the lab that resembles a light table appears to effortlessly recognize each of the photos in a digital album and sorts the images into proper "piles" based on location, person, and activity. The same table then correctly sorts information within dense legal documents as part of litigation research. The data can be compiled, emailed, and routed in virtually any way imaginable. For a data guy like ACS's Blodgett, it was love at first sight. "I was already happy with our technology," he says. "But this was going to make an immediate difference to us." When Blodgett and Beltrametti talked about EZPass, the automated-toll-collection technology that ACS oversees, it became even more obvious. As Blodgett explains, EZPass transponders--those plastic rectangular blocks--can often get lost or broken. When he asked Beltrametti if Xerox had a machine that could read a license plate--thus eliminating the transponder entirely--she told him yes, and then upped the ante. "'Would it help you if it could read the registration as well? Or if the license plate was held on by wire instead of a bolt?'"--a sign that the car might be stolen. Blodgett was impressed. "I told her yes it would. It would help me a lot."

Already the marriage has shown results. A new Xerox device--a compact computer with scanning, printing, and Internet capabilities--has been deployed to ACS insurance clients for use in the field. Instead of being mailed, claims and related data are scanned on-site, sorted, routed, and put immediately into a workflow system. Error rates have plummeted along with processing time. That idea, and others in the pipeline, came from "customer dreaming sessions," which Blodgett has been coordinating at PARC, in Palo Alto, and other Xerox research centers. Essentially, he is bringing his humdrum customers--procurement managers, payroll officers, and municipal officials--to meet his new, cool genius friends.

Stephen Hoover, CEO of Xerox PARC, paints a utopian picture at a roundtable meeting at PARC, with his boss, Burns, at his right hand. To Hoover, PARC can already make ACS more efficient. But soon, it can make ACS smarter, too. "It's not just processing Medicaid payments," he says. "It's using our social cognition research to add wellness support that helps people better manage conditions like diabetes." Or it involves analyzing patterns and applying the results to, say, the real-time parking and traffic data that ACS collects for municipal customers. Hoover ticks through a list: road sensors that help you find a parking spot or ticket you when you go too fast, parking meters that call 911 and take photos when a button is pushed. Some of these technologies are already in beta in cities such as San Francisco and New Orleans. "Look," Burns chimes in, "not everything that happens here makes it to the marketplace. But PARC now has a model that allows them to dream beyond the boundaries of what Xerox can use." Hoover appears to be holding his breath as she continues. "What happens now is the ability to apply some of that dreaming that was done for other clients."

One of the most interesting things about becoming a CEO is that the very thing you did to get there is usually not the thing you need to do to keep you there. Burns still doles out radical honesty when needed. But there's now an overlay of Zen that seems to surprise even her. She has become a listener-in-chief, she claims. And she has learned to temper her outspokenness--with the help of some good coaching, she admits, from her business associates.

Xerox's PARC research center has already developed a host of technologies to transform the service industry--parking meters that can call 911 and road sensors that ticket you if you go too fast.She is philosophical about her company's transition from tech titan to back-office Big Brother. The first xerographic machine, the 914, was a miracle of technology and made its debut in the ballroom of New York's Sherry-Netherland Hotel. Today, few people notice whether the machines in the corner copy room are from Xerox, Ricoh, Canon, or HP. Fewer still know that the company that brought printing to the masses is now working behind the scenes, digitizing the paper it once pushed. It's a massive identity shift that Burns seems to have fully embraced. "Look, it's cool to be Google," she says. "But even Google has to close their books and pay their people." The work isn't glamorous, even for companies who specialize in it. Nor is it easy. Xerox has been battered by a weak global economy and supply interruptions due to the Japanese earthquake. And its stock price has hovered in the single digits for the past year. Yet as contrarian strategies go, there are some reasons to be cautiously optimistic. As of now, Xerox has close to $1 billion in cash on hand, a far cry from the near-death experience of a decade ago. And almost half of its annual revenue derives from services, giving the company a nicely diversified revenue stream. "We see now that the ACS acquisition was probably a very forward- looking, prudent move," says Deepak Sitaraman, a Credit Suisse analyst. He adds that Xerox appears to be on track for 5% growth next year.

Burns, too, has come a long way from the Lower East Side. She may enjoy the occasional jab at the President, but she clearly admires him. And, like Obama, her accomplishments have earned her an access that she could never have imagined. In addition to her work on economics, she was tapped, in 2009, to be on the White House Committee on Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math Education (STEM) with former Intel CEO Craig Barrett and former astronaut Sally Ride. She works a plea for STEM education into every speech. When I ask if all the time she has spent in Washington might tempt her into the public sector, she laughs, then rolls her eyes. "Things move too slowly in government." Instead, she talks about her old neighborhood and jokes that she can't afford to live there anymore. "But there are plenty of neighborhoods just like it, all around the country," she says. "I see kids out there, nowhere to go. Nothing good waiting for them. Any one of them could have been my son." She stops to think. "Or me."

A version of this article appears in the December 2011/January 2012 issue of Fast Company.