In Mexico, blogging or leaving a comment online about narcogangs can get an Internet user--even an anonymous one--beheaded, tortured, and mutilated. Here's a look at the new digital front in the country's brutal, escalating drug war.

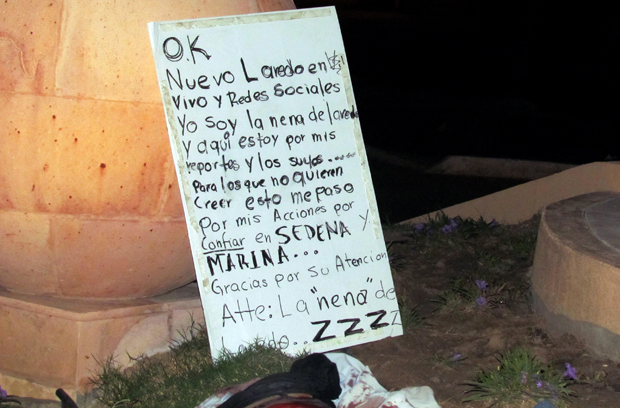

In late September, police found the body of Nuevo Laredo resident Marisol Macias Castenada, a 39-year-old office manager for the city's Primera Hora newspaper, dumped on a bridge about a mile from the U.S. border. Her decapitated head was on a rock nearby. A sign left next to her body referred to what her killers believed was her online identity, Laredo Girl. "... I'm here because of my reports, and yours," the sign stated. "For those who don't want to believe, this happened to me because of my actions, for believing in the army and navy. Thank you for your attention, respectfully, Laredo Girl ... ZZZZ." The "Z"s were the calling card of the Zetas narco gang, who claimed responsibility; the Zetas believed she was reporting news about gang activity not for Primera Hora but on the Nuevo Laredo Live web forum. They had traced the pen name back to Castenada.

It was one of three prominent killings of Internet users to reach mainstream media reports. Killing of anyone believed by narcogangs to be an opponent is one of the hallmarks of the epidemic of drug-related violence that has cost more than 35,000 people their lives in the past five years--many of them were civilians who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Just this past August, gunmen in Monterrey sealed the doors and set a casino on fire during business hours, killing at least 50.

But the fact that narcogangs are having in-house geeks ferret out anonymous social media commenters signals a deadly new digital evolution. Gangs such as the Zetas regularly monitor social media, especially the local web forums where so much hyperlocal news is disseminated. (It's a tactic used by The People's Republic of China for aggressively scouring Chinese-language microblogs for political content and even by the New York Police Department, who've been criticized for monitoring local restaurants and websites to gauge the political involvement of the city's Muslims). But in Mexico, media monitoring is a precursor to murder.

Narcos even sometimes use the same social media to send a deadly message. Apart from Castenada's decapitation, a widely disseminated viral video showed a man being castrated, decapitated, and hacked into pieces by masked men in military-style clothing [Ed. Note: Warning, you can't unsee this]. As one New York-based figure with knowledge of the situation in Mexico tells Fast Company, “Utimately people are getting killed regularly for 'talking,' and the narcos seem pretty agnostic as to whether that talk is online or off.”

Regular killings and death threats against Mexican reporters and media professionals--more than 80 have been killed since 2008--has all but stopped aggressive narcogang coverage by print and TV outlets. Most publications that cover narco news, such as the prestigious Proceso, do so in non-bylined articles.

Instead, the job of monitoring the lurid violence and regular havoc of the narcogangs has fallen to an active community of Twitterites, YouTube users, bulletin board posters, and “narcoblogs” such as the popular (and well protected) El Blog del Narco and Narco Trafico en Mexico.

Within Mexico (and worldwide), El Blog del Narco is an enormously popular website. According to Alexa, it is the 59th most visited website and it cracks the top 5,000 most heavily visited websites worldwide. There have been persistent rumors that the site, whose anonymous operators have so far escaped operation, enjoys some kind of narcogang or government protection.

“The factors that are remarkable about the narcoblog phenomenon don't exist together in any other current expression of media," Boing Boing's Xeni Jardin, who has reported regularly on narcoviolence, tells Fast Company. "You have the threat of horrific, violent consequences for publishers, if their activity falls afoul of cartel (or perhaps police or army) approval. You have huge, huge traffic and correlating ad revenue. The public is hungry for the information they publish as a matter of their own life and death, and the content is published incredibly fast and wide--but the content is traumatizing."

Meanwhile, American print, web, and television media have largely ignored the massive wave of Mexican narcoviolence. This is despite the fact that many of the worst attacks (such as the Nuevo Laredo social media killings) take place within a half hour's drive of the border. There have been rare exceptions such as Boing Boing, and newspapers in cities with large Mexican diaspora populations such as the Los Angeles Times and border publications such as the El Paso Times have consistently provided excellent coverage. However, most coverage of the Mexican narcogangs in the United States press is limited to novelty pieces about private drug cartel zoos and drug-trafficking submarines.

The big question that observers have been curious about is whether, given the porous nature of the Mexican-United States border and the narcogangs' extensive ties to the U.S. underworld, violence could spread into El Norte on a mass scale. There have already been isolated attacks in Arizona and Texas, and an American consular worker was the subject of an attempted hit from the Sinaloa cartel. Ironically enough, Mexican narcogangs appear to be a greater threat to American homeland security than the Middle Eastern terrorists who dominate the popular discourse.

It is in the interest of the narcogangs to avoid bloody violence in the United States; the world's dominant military power does not take kindly to cross-border violence and the DEA already has a massive armed presence in Mexico. However, mistakes do happen. One hot-tempered hitman could lead to mass hysteria and harsh reprisals if, say, a United States shopping mall or resort hotel was targeted.

A recent Microsoft Research Report on Mexican Twitter habits found that international media outlets such as Al Jazeera and The Guardian gave far more media coverage to narcoviolence than their American counterparts, despite the fact that much of the worst violence took place a skip and a jump from the Rio Grande. The lack of coverage is surprising given the ramifications for the United States.

The major issue for the narcogangs is that Mexicans are not only using social media to spread news of atrocities and “no-go zones”; they're also using it to organize. After the casino fire in Monterrey, a series of Twitter hashtags such as #CasinoRoyale, #FuerzaMonterrey, and #SiNoPuedeRenuncien were used to express widespread outrage and condemnation. In border cities such as Nuevo Laredo, websites such as the previously mentioned Nuevo Laredo Live play an important part in community organizing. Even the Mexican government has turned to social media to fight the narcogangs, with an anonymous tip system and a series of charming anti-narco YouTube comicbooks.

[youtube wyb6VXsyIRQ]

In the end, fighting the wave of narco violence will require dedicated law enforcement, anti-corruption efforts, brute force, detective work, and bravery that's goes far beyond social media rebellion. But tragically for now and the foreseeable future, narcos are the ones most effectively transforming online chatter into action. Murder, to be precise.

[Top Image: Getty Images; middle Image: WM Consulting]

For more stories like this, follow @fastcompany on Twitter. Email Neal Ungerleider, the author of this article, here or find him on Twitter and Google+.