Do games have any place in the training of future journalists? This reporter stages a challenge to students to find out.

This fall, I began layering in game mechanics into a graduate journalism course I teach at New York University. In it, students vote for the best stories we workshop on a given day, and the winners receive prizes (like Slinkeys, yo-yos, plastic dinosaurs, maybe SweeTarts or Skittles). I plan to post a series of social media leader boards on our Facebook Group page to show whose Twitter presence (increase in the number of followers, number of clicks from Twitter to their blogs, etc.) has grown the most over a given time. And through a company called Stray Boots, I organized a Wall Street treasure hunt, in which students learned the history of the area through playing a walking game. So far, four weeks into the semester, these games have proven popular.

Don't think I'm dumbing down the course for the Millennial generation. It remains a rigorous six-hour writing and reporting class that teaches the fundamentals of hard news and deadline reporting--with a business focus--for newspapers, wire services, and online news, as well as data journalism, interview techniques, the basics of multimedia, ethics, media entrepreneurship, and a host of other topics. Over the course of a 14-week semester students will hand in more than 20 assignments, almost all of which are critiqued and line edited. Plus they maintain their own blogs, keep track of their metrics, and engage in social media. But as any professor will tell you, it can be difficult to engage students, especially in a class with such a challenging course load. Burnout, in the past, has been a problem.

Because I'm researching a book on how game mechanics are expressed in everyday life for Porfolio, an imprint of Penguin, I realized the classroom would be an ideal incubator for gamificiation. (Food for thought: The iPhone auto-corrects "gamification to "ramification." Hmm.) There's evidence to support this. A report from the 2006 Summit on Educational Games by the Federation of American Scientists found that students recall just 10% of what they read and 20% of what they hear. If there are visuals accompanying an oral presentation, the number rises to 30%, and if they observe someone carrying out an action while explaining it, 50%. But students remember 90% "if they do the job themselves, even if only as a simulation." So I began ginning up an experiment, based on Stray Boots' treasure hunt.

In the second week of class I met my 15 students in front of Manhattan's Trinity Church, just a few blocks from Ground Zero. I divided them into three teams of five, and each chose a leader to operate the smartphone to receive each question. The students shambled around lower Manhattan, collectively trying to answer questions, which ranged from how many floors below street level are the gold vaults of the New York Federal Reserve Bank (five) to the color of the World Financial Center's roof (green) to who is buried in a particular pew in Trinity Church (Alexander Hamilton). It took each group about an hour to answer 15 questions. The following week I gave students a written test. I wanted to find out what students would remember better: The answers to 10 questions from the treasure hunt from a week earlier, or a short reading passage (about 450 words) on the history of Wall Street they read twice in the span of four minutes.

The results were notable. Collectively, my 15 grad students correctly answered 77 out of 150 questions (or 51.3%) from the reading passage but for the Treasure Hunt they got 89 of 150 right (or 59.3%). In other words, students had higher recall of a game they had played a week earlier than the a short passage they read a few minutes earlier. Sure, 8% isn't a huge difference, but I think it's significant.

More striking, the students who operated the smartphones did the best of all on the Treasure Hunt questions. One student got 10 out of 10 on the Treasure Hunt questions but only six right on the reading passage; another answered seven correctly on the Wall Street game but only two right on the passage; the third did equally well on both tests. It appears the people most engaged in the game had the highest retention rates of all.

When I told Avi Millman, the 28-year-old cofounder of Stray Boots, my findings, he wasn't surprised. A former math teacher of his used Stray Boots to help her design a mathematics walk. In one instance she took a group of middle-school students around Greenwich Village and had them, for example, measure the Washington Square Arch's area in square feet. She also found that students were more engaged and seemed to enjoy learning more.

A Princeton graduate, Millman came up with the idea of gamified walking tours in the summer of 2008 while visiting Rome. Like many travelers he relied on a drab guidebook but realized an interactive tour would be much more fun. Today Stray Boots charges $12 for gamified walking tours in 10 cities, including New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and is expanding rapidly. The company's latest is a tour of Portland Oregon's microbreweries. Millman and his cofounder Scott Knackmuhs initially bootstrapped the company and relied on some family money. Now headquartered in a one-room office in Downtown Brooklyn with five employees paid "ramen noodle low salaries," it's profitable, and Millman says he'll soon seek a series A funding.

Of course, my little test that Stray Boots helped me concoct is by no means scientific, but it does show promise for so-called serious games: Students at more than 1,000 colleges and universities play an IBM "sim" called Innov8 to practice running virtual businesses. Quest to Learn, a noncharter public school for 6th to 12th graders in Manhattan, bases its entire pedagogy on game design. It seeks to have children assume the roles of truth seekers--explorers and evolutionary biologists, historians, writers, and mathematicians--and engage in problem solving. There are no grades. Students are rated "novice," "apprentice," up to "master." A class might be devoted to engaging in a multiplayer game and working in teams to defeat hostile aliens or becoming immersed in a "sim" game and running an entire city. The kids even code their own games, which involve math, English, computer science, and art.

While I'm not ready to jettison our curriculum and create a completely game-based approach to journalism, I'm willing to experiment. If you have any suggestions, fire away in the comments section.

Adam L. Penenberg is a journalism professor at NYU and a contributing writer to Fast Company. Follow him on Twitter: @penenberg.

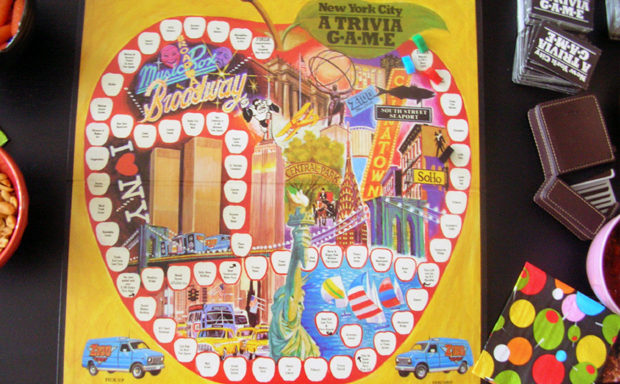

[Image: Flickr user duluoz cats]